Georg Kolbe "Liebeskampf"

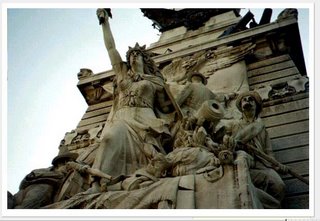

This overly ambitious entry reproduces -- in its entirety -- the chapter that Lorado Taft devoted to Germany in his book "Tendencies in Modern Sculpture" (which had three sections: France (where he studied) -- Germany --- and everywhere else)

He soundly condemned the flamboyant excesseses of 19th C. French sculpture --the kind that led Baudelaire to write his famous screed "Why sculpture is boring"

-- but he didn't much like the simplified school that became trendy in the early 20th (Maillol, Despiau )either. If a culture is best seen by how it envisions the divine -- one might say that Taft just could not share French ideals --so when he tries to recreate some typical nymphs dancing around a fountain --

they might just as well be nice American sorority girls at a toga party.

Meanwhile, he consistantly condemns German work for its ideosyncratic ugliness ("paroxysms and strivings for originality").

But he certainly gives it a lot of attention -- especially to Metzger -- where he finally confesses: "If I seem to give undue space to the often grotesque and enigmatic art of Professor Metzner it is for the reason that he is a commanding and a characteristic figure in German sculpture" (while we can note that he has no commensurate interest in the commanding figures of British, Spanish, Italian, or Scandinavian sculpture)

In other words -- he was in transition himself -- and not really sure -- all the time -- what he really liked.

As with my other posts on Taft -- my comments will appear in yellow beside the original text -- and readers are invited to post their own comments (and forward their own pictures !)-- which will later be posted next to the text and pictures to which they refer.

In other words -- I see this as a work-in-progress.

Like most of my generation who received their art training in France, I long cherished a profound disrespect for German art. One of the most painful results of war is its heritage of hate and misunderstanding between sister-nations,and the Franco-Prussian War was peculiarly productive of this lamentable harvest. For years German art was never seen in the exhibitions of Paris and it was always referred to with contempt. I recall the surprise and almost unwilling delight afforded us by the first German painting which appeared at the Salon in the early eighties - a tender yet masterly conception of Christ amid modern surroundings exhibited by Fritz von Uhde under the title: "Komm, lieber Jesus, sei unser Gast." The picture had a great success and was followed by a flood of Gallic imitations which have ever since held permanent place in the Parisian studios and exhibits.

German sculpture remained unknown to us. What the magazines brought to view showed as a rule the pompous art of officialdom or else hopeless anachronisms -belated survivals of "the mode" of Canova and Thorwaldsen, without their touch of genius.

With vague, unhappy memories of such attempts, and particularly of the ornate grandiloquence of certain imperial monuments in Berlin, the traveler is amazed to discover that some of the most interesting works of sculpture and architecture recently produced in Europe are to be found in the growing cities of the German Empire. There is a saying that "when things become as bad as they can, something has got to happen." The something has happened in Germany, and the pretentious allegories of the nineteenth century are giving way before the thoughtful work of a younger generation who have in mind, first of all, the reasonable use of the medium concerned; who treat stone as stone and bronze as bronze, producing delightful results with an astonishing economy of effort.

This is Taft the modernist: condemning "pretentious allegory" and celebrating "stone as stone, bronze as bronze" Of those who have prejudiced the world against German monumental art none can lay claim to greater eminence than

Rudolph Siemering (1835-1905) and Reinhold Begas. The first was a delightful old blunderer who produced one or two respectable things, but whose work as a rule was utterly devoid of both charm and distinction.

Hochmeister vom Alten Fritz (Siemering)

Albrecht Von Graefe (Siemering)

To select a work like the Bismarck monument at Frankfurt as representative of his life's achievement does not seem quite fair, but this group is neither better nor worse than Siemering's average. Bismarck leads Germania's fiery steed with one hand and grasps his sword with the other, while the enemies of the Vaterland are personified by a grotesque dragon, conveniently placed for trampling under foot from time to time. Siemering's monument to Washington in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, is known all ,too well, although you may not have noticed Washington himself, lost as he is amid a comprehensive collection of American fauna done into German bronze!

Base of the Washington monument (Siebering)

And then in the midst of your vituperations you run across a portrait of the man and find that Rudolph Siemering was one of the handsomest and most intellectual of all his race! He had a noble brow and long silvery hair and beard, and a kindly, yet earnest expression-I am sure we should have loved him had we known him. It was his mistake to be born at the wrong moment and to learn his craft in a period of transition. He is already quite out of date.

Taft the modernist -- yet again -- where "out-of-date" is the kiss-of-death. What's wrong with Siemering ? I think he typifies the non-aesthetic of mid-19th C. (or late 20th C.) American sculpture -- i.e. leaving no detail unexplored -- especially painful in the dead space between the multi-piece toy-like figures of his complex tableauxHe is amusing: “Delightful old blunderer”; “Conveniently placed for trampling,” etc --Marly

Begas

Begas

Begas

Begas

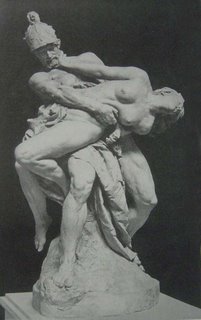

Begas had perhaps no better taste, but he was a clever modeler and possessed a certain decorative skill which made his pompous, superficial art very welcome in the early years of the imperial regime. Among his ideal works we find a perturbed "Susannah" and an uncomfortable group of "Hermes and Psyche" on their travels, also a very strenuous "Rape of Sabine Women," which seems to have been particularly admired. In a single park in a German city I noticed three groups portraying this primitive and time-honored form of endeavor.

Very funny ! Yes -- only the brutal Hun would celebrate rape in a public park -- except that --- I really like this Begas statue ! It's the battle of the sexes -- just like

But it is in his big official works that Begas best expresses the bluster and intolerance of a government founded upon military ideals. His monument to the first emperor of Germany, William I, has been described . as " surrounded by floating Victories, roaring lions, standards, cannons, and chariots." It is not without its admirable bits of modeling, but as a whole it is lacking in distinction and particularly in that sense of repose which is the very essence of great sculpture. The horse and rider are sufficiently dignified, the Victory not ungraceful, although-never to be mentioned with such a "Victory" as Saint-Gaudens gave our General Sherman. But after this the monument becomes a pretentious jumble upon which the busy artist has piled all the stage properties within reach. His spotty reliefs are abominable, with their lonesome figures afloat in vast landscapes. The warriors are well enough modeled but are perfectly adventitious in the design. They sit down or recline upon the steps wherever "that tired feeling" strikes them. There is nothing organic in the composition of this monument; nothing sculptural in its development. The favorite court sculptor triumphantly shows us how not to do it!

What shall I say regarding the much-discussed "Sieges Allee"? That it is monotonously arrogant goes without saying. But even its tiresome advertising of the Hohenzollerns is not uniformly bad. Thirty-two monuments there are, symbolizing thirty-two generations of men with their ambitions, their struggles, and their bitter disappointments. The sequence of lives is to me ever inexpressibly pathetic, and this array of monarchs who have lived and loved and hoped and feared gripped me strongly. As usual, the mad Kaiser was impatient and unreasonable; the workmanship is more or less hasty and so realistic that the marble chains almost rattle in the wind. Clever Italian carvers were employed who delighted in attenuating the stone to the last degree. But the tooth of time will improve all this, and some day when these effigies have become as venerable as the men they portray, the "Sieges Allee" may be held in great reverence like Maximilian's Tomb at Innsbruck, with its host of honored guests of bronze.

A reasonable explanation for the mediocre public sculpture of the Bourgeois era: the cloddish patron

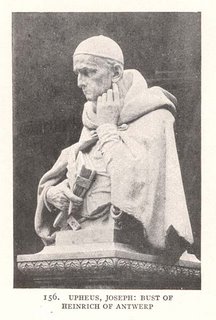

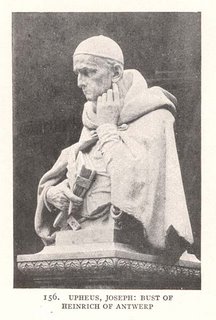

Each figure of a ruler of Prussia is supported by two busts of leading men of the reign. Some of these are admirably vivid interpretations, one of the best being the ("Heinrich of Antwerp" by Joseph Upheus (1850-1911)(Fig. 156).

I really like these pieces by Upheus -- but would be surprised if his work has ever entered an American museum

I like some of the small bronzes a lot—the little Stuck “Amazon” and the Upheus archer (such a sleek burnished line.)..Marly

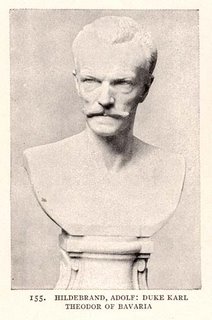

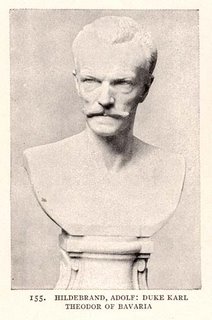

Among those untouched by the new movement the great name is Adolf Hildebrand , of Munich, a master of the old school and Florentine tradition, whose example has been a constant gospel of good taste and sanity. Even today, when the whole world seems to have gone after false gods, his influence continues to be felt, and I wonder if the fact that in the midst of this revolution German sculpture, however fantastic, remains essentially sculpture, is not due largely to the life-long precept and practice of this admirable representative of the craft.

He is a poet and philosopher as well as sculptor and has written works upon the underlying principles of his art, particularly upon the requirements of monumental design. It is a pity that so few artists have bethought themselves to give this subject serious consideration.

More evidence for the importance of Hildebrand in the sculpture world of his time -- probably every serious student considered reading "The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture"

Hildebrand was born in 1847 in Marburg. He studied in Nuremberg and later in Munich and enjoyed the inestimable privilege of a sojourn in Rome and Florence with cultivated companions of high ideals. His early portraits showed a startling realism: a bust of “Frau Fiedler," done in 1876 in colored terra cotta, is a presentment so strangely lifelike that it would really inhabit any room in which it were placed. An achievement of greater significance is the well-known marble bust of Duke Karl Theodor of Bavaria (Fig. 155),

which along with extraordinary fidelity to the individual offers a just balance of animation and repose. The union of these two seemingly contradictory qualities in a harmonious combination is the greatest problem of the sculptor. No modern has succeeded better than Hildebrand.

A nice way of putting it. Another word for it might be "tension". It's the pieces that lie flat and dead that have given figure sculpture such a bad reputation.

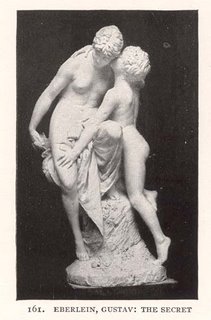

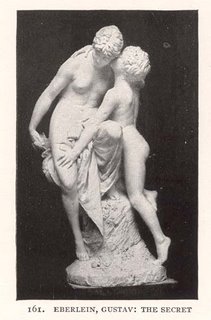

Very much less important but likewise outside the present movement which we are about to discuss is the once popular Gustav Eberlein (1847-1926), a survivor of the Romantic school. Elegance and skill reveal themselves in all that Eberlein does, but there is something of the picturesque -a note almost annoyingly operatic, one might say-in his work, which does not make for great, genuine sculpture. "The Secret" (Fig. 161) is one of his best productions.

I have a hard time with the saccharine unless it's really magical -- and prefer this bronze figure -- and generally prefer German sculptors when their figures are male.

The struggles of the closing years of the nineteenth century - the efforts of German sculpture to escape classic and romantic traditions-left a bewildering if not pleasurable record. While the majority and particularly the leaders were doing such monuments as we have seen and such fountains as Otto Lessing's (1846-1912)

Genius of Humanity (1890)

Genius of Humanity (1890)

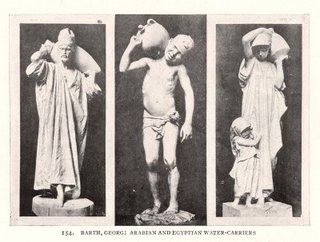

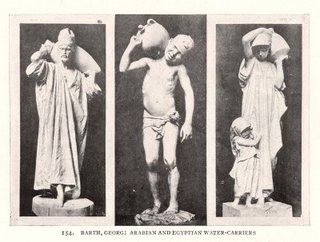

agonized "Prometheus" group in Berlin, the younger men were becoming very restless and insurgent. Some, like Carl Georg Barth, turned to the Orient for their themes and were well rewarded (Fig. 154).

Georg Barth

Georg Barth

Ouch -- I can't see how those "oriental figures" are any better than all the other overly-descriptive figures of the 19th C. -- but I do like the little cupid -- as a few steps above a typical doll

The cupid-with-orb would look marvelous in my cottage garden, and probably be stolen by a passing tourist.--Marly

Others tried fantasy, as Rudolf Maison with his freakish "Faun Girl," and Otto Lang, who devised a remarkable "Faun Skating." Perhaps the most extraordinary of this series is a group called "At the Bottom of the Sea" by Otto Petri.

Nök vom Meeresgrunde, 1907

Nök vom Meeresgrunde, 1907

Something about the beauty and the sea-monster really appeals to me --- even more than the statuary rape-scenes -- and it seems so right in the middle of a river

The-Creature-from-the-Black-Lagoon-and-beauty “absurdity” by Nök vom Meeresgrunde would be marvelous somewhere between the mouth of the Susquehanna and the arched, crenelated Clark bridge—perhaps about a hundred yards upstream. -- Marly

Just where this absurdity would find a welcome it is hard to say-:possibly in the depths of an aquarium or as an understudy to Annette Kellerman.

Returning to themes more sane we find in the "Adam and Eve" (Fig. 162) of Peter Breuer (18656-1930) an almost perfect example of sculptural compactness. Scrutiny of the marble discloses that its modeling does not quite equal the composition, but this group is deserving of great respect.

I wish I had better pictures of this so I could see whether I agree or not. Both of these Breuer pieces seem to lack that extra spark

Peter Breuer - "Woman with mirror"

Peter Breuer - "Woman with mirror"

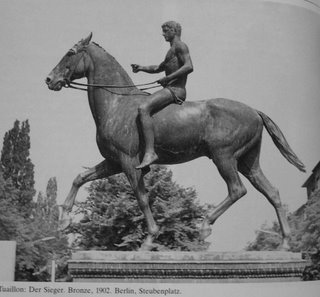

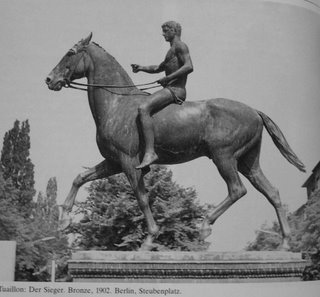

One of the excellent sculptors of Germany, an artist whose work is never sensational, bears the French name of Louis Tuaillon. His" Emperor Frederick III" at Bremen (Fig~157), although at first sight a bit old-fashioned in his Roman armor, is nevertheless a statue of sterling quality. His "Amazon" (Fig. 160) occupies a prominent position in Berlin and is the acme of quiet grace. You may not care for it at first, but you return to it with increasing pleasure until in time it becomes a habit.

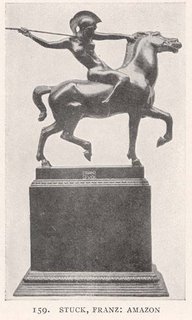

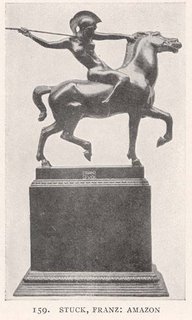

But they all make "Amazons" as well as fauns over there! Franz Stuck, the eccentric painter, often turned to sculpture for the expression of his weird and crowding thoughts. His small equestrian "Amazon" (Fig. 159) is happily conceived-much better art indeed than most of hjs paintings.

I really like those Louis Tuaillon equestrians and hope I can see them some day. Will they join the elite triumvirate of great equestrians ? (Marcus Aurelius -- and the soldiers done by Donatello and Verrochio) I need to see some other views !.

But I have seen the Stuck piece -- there's a cast at the Art Institute -- and I agree with Lorado that it's better than his painting. It's really kind of amazing that a guy who never sculpted did such a fine piece

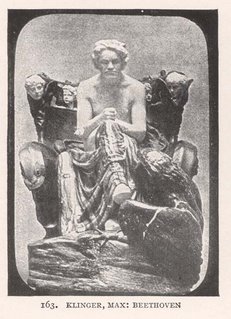

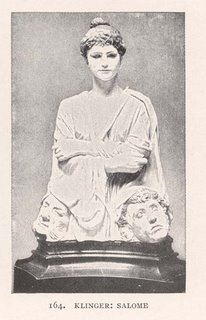

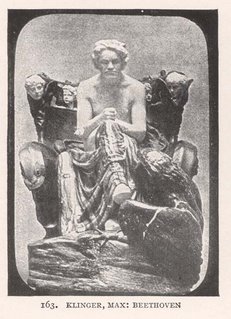

One of the greatly advertised productions of' recent years was Max Klinger's (1857-1920) elaborate "Beethoven" (Fig. 163), a work of some merit but executed in a confused combination of metal and various stones.

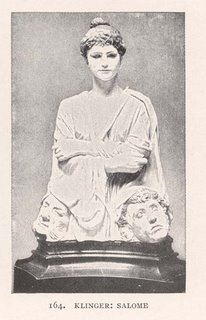

Beethoven is almost forgotten,. such is the display of handicrafts; one longs to see the model in the unity of the original white in order to judge it as sculpture. Klinger's colored "Salome" (Fig. 164) in Dresden is startling in its realism, while an "Aphrodite" in the same collection is nude life itself-realistic modeling reinforced with the tints of nature.

Again -- I agree with Lorado -- that Beethoven piece has kitsch written all over it -- but the color photo beneath it -- of the lady in a green gown -- that actually looks quite appealing. "Many a green gown has been given, Many a kiss, both odd and even" (Robert Herrick)

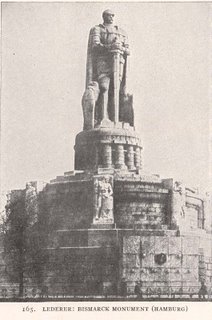

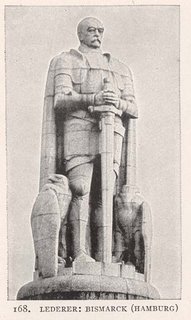

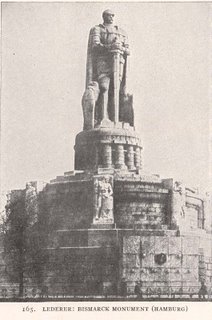

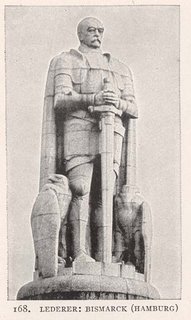

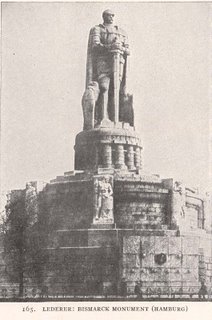

We turn now to something far more important, a monument at Hamburg of great originality and power. So strange is its aspect that a word of explanation is necessary. In many towns of Germany one finds a queer, primitive, weather-beaten figure of Roland, the traditional hero and protector. These ancient effigies are looked upon as almost sacred; their service as guardian sentinels is everywhere recognized. Hugo Lederer, an Austrian by birth and education, has created upon this familiar motif a memorial to Bismarck (Figs. 165 and 168),

Detail of Bismarck monument

Detail of Bismarck monument

which is one of the truly great monuments of later times -an armored figure of colossal size standing guard upon the hilltop and supported by massive architecture of which it forms a part. The statue is vastly impressive because it was conceived "big" instead of being an ordinary portrait enlarged. An appreciative writer says of it: "No attempt has been made to obliterate the fissures between the granite blocks that compose the mighty figure; each block is seen in clear outline, and thus the whole structure appears almost as the result of the upbuilding forces of Nature herself. Power in calm repose-that is the impression which forces itself irresistibly upon the spectator! We of a modern world find ourselves out of sympathy with the methods of Bismarck, but we must recognize that like the man thus honored the effigy stands grim and faithful, admirably adequate.

Wow ! I sure don't get "power in calm repose" -- so well achieved in ancient Egypt -- from these photos -- I just get "Big toy soldier" -- although, I admit, I also think it's subject -- both as a specific historical actor and as the ideal of German militarism -- was largely responsible -- along with Lenin -- for the disastrous 20th Century.

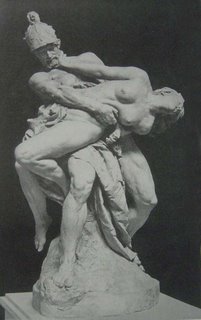

An early work by Lederer, called "Fate" (Fig. 169), reveals the dramatic instincts of its author. This symmetrical group is composed of three figures, a gigantic and portentous female and two helpless men whom she drags by the hair. Possibly the sculptor had a secondary purpose, showing how" mere man" will fare when the sexes become properly adjusted!

Hah ! I'm tending to agree that fate is a big, strong, not-so-attractive woman who drags men by the hair. That's the Greek and German tradition -- maybe the rest of the Indo-European world as well.

Not so sure that I believe Lederer’s “Fate” is a woman, though you are funny about her. She looks entirely too mannish, beyond the demands of monumental; perhaps it’s the photograph.--Marly

Public TV just aired the Lynn Webster Wilde documentary On the trail of the Warrior Women, wherein a Sarmatian skull -- identified as a female warrior -- was digitally reconstructed to reveal an image almost identical to the head modeled by Lederer. You've never seen a woman look like that ? She also happens to resemble the 19th C. photo of my great-grandmother!

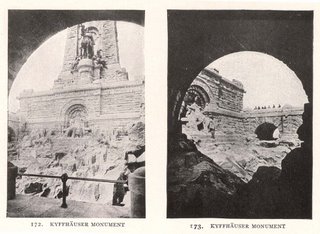

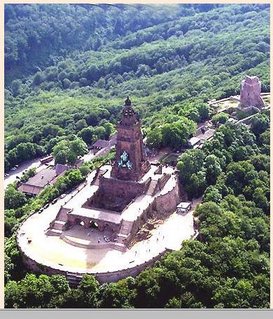

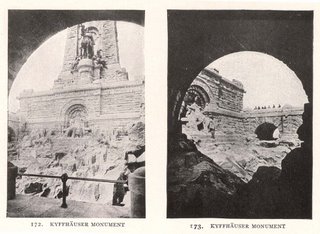

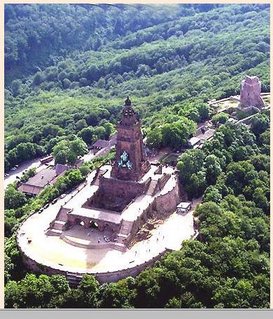

The Kyffhauser Memorial (Figs. 172 and 173) owes its impressiveness to the architect rather than to the sculptor's contribution.

It is one of the notable works of Bruno Schmitz-the designer of the Indianapolis soldier monument-

The Indianapolis monument is conveniently located near the Greyhound Bus Station -- so I've had the chance to see this piece many, many times at odd hours of the morning and night. It's so well made -- but so depressing at the same time -- since all its diligent detail is not pulled into that fine, happy movement that Italian sculpture has taught us to enjoy. But, until now, I never knew the sculptor was German -- or that he made that magical mountain in Germany -- that seems so much better suited for the cover of a black-metal record album.

Thank goodness this kind of fanciful militarism has been marginalized into the world of frustrated adolescent boys

who has here evolved a massive tower along with its protecting arcades of heavy masonry, directly out of the mountain quarry which gave them birth. One looks through the arches across a field of rugged rocks to where reposes in his subterranean stronghold ':Der alte Barbarossa, der Kaiser Friederich." Above this recess, upon the side of the tower, appears the gigantic equestrian statue of the founder of the new empire, William I. Despite the inadequacy of this portion of the sculpture the conception as a whole is grandiose.

Yet another of these massive piles which the Germans delighted to erect all over their land in celebration of the new empire is the monument to Emperor William I at Coblenz. The almost Cyclopean architecture may be imposing upon near approach, but the silhouette of the sculpture is so absurd that the work was taken by our boys in khaki as a colossal joke.

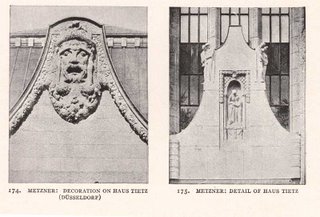

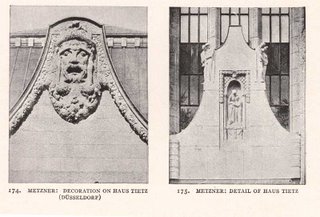

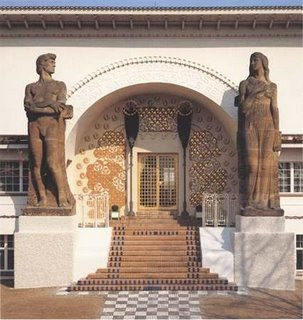

The old-time city of Dusseldorf, associated in most of' our minds with an extinct school of Romantic painting, offers us today one of the finest examples of modern architecture and sculpture blended in happy union. It is only a department store, a "Siegel. & Cooper's," called the "Haus Tietz" (Figs. 174 and 175),

but its design is really notable. Until recently our own architects have seemed possessed of a desire to minimize the height of their lofty structures by stratifying them, cutting their fronts with as many horizontal stripes or ruffles as possible. In the building under consideration the designer has frankly acknowledged its height, and, with a perfectly practicable plan, has developed an effect of soaring which is very happy. Its ranks of graceful. piers suggest a great pipe organ. Its sculptural adornments are not the casual groups and figures that are set upon shelves on our facades, but are, as it were, an efflorescence of its rough stones, sparing in number, but holding the right proportion to its restful surfaces. Like the design as a whole, they are organic, growing out of the very structure itself. Its treatment seems to have been dictated by the stone of which it is made; respecting its material, it is exalted by it.

Such work as this, so new, so independent, and so delightful, recalls the dictum of Mauclair that one should be as concerned in how he is going to do a thing as in what he is to do; in other words, that the treatment merits no less thought than the subject itself. This is a matter which we Americans have always been disposed to overlook.

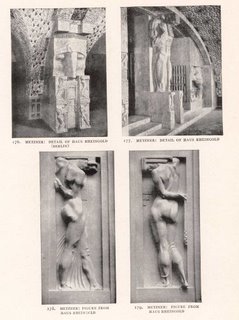

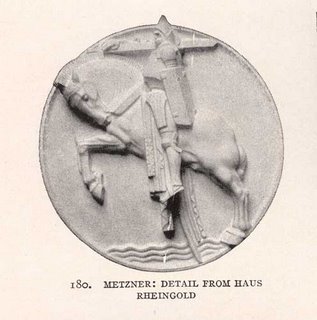

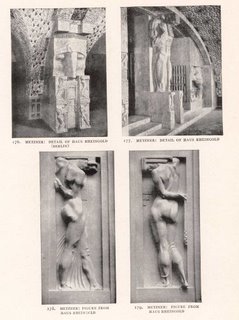

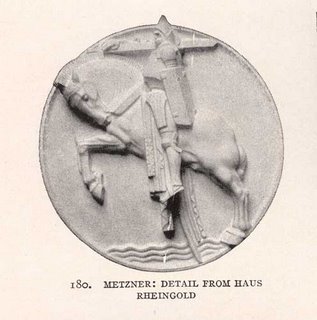

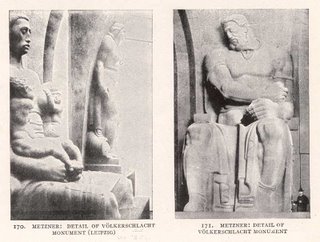

Another interesting combination of sculpture and architecture is found in that extraordinary restaurant of Berlin called "Rheingold Haus," where Professor Franz Metzner, another Austrian, has produced a series of weird and strikingly original effects (Figs. 176-80).

He uses the human body as others employ plant forms, conventionalizing the figure, amplifying it, and now and then compressing it into unwonted spaces, but always with a pattern so essentially decorative and a touch so sure that one is compelled to recognize his authority. He is master here, and these are his creatures to obey.

Arbitrary and whimsical uses of the figure which might easily lead to extravagances in other hands or in other places seem admirably suited to this pleasure resort, where monstrous heads peer out from shadowy corners, brawny giants uphold the masonry of the walls, and lithe-limbed Rhine maidens gleam through billows of tobacco smoke. Yet with all this prodigality of invention, this bewildering versatility and power, there is no effect of lawlessness, of riotous excess. Bronze and stone and wooden panels are treated according to the demands of the materials and the severe requirements of architecture. The directness and thrift of means here shown, the austerity of design, contribute to a result which is legitimately sculptural.

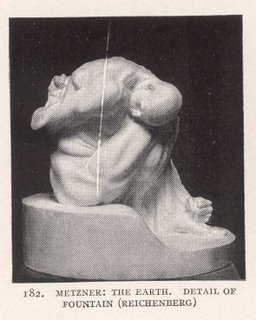

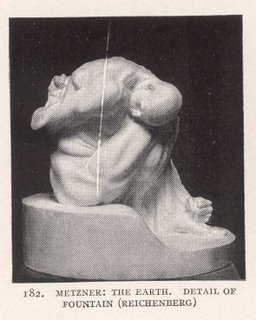

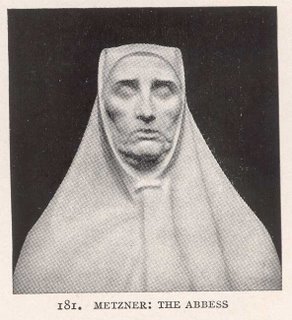

Professor Metzner (1870-1919) has been indefatigable. Among his many works one may mention likewise a fountain at Reichenberg, of which we show a detail, the powerful figure called "The Earth" (Fig. 182);

I think Taft admires Metzger, but doesn't like him -- which may just mean that he dislikes him -- but can't explain why. Maybe it's because Taft is just not German enough -- which would seem to be reason enough for me.

a conception of a medieval warrior, "Otto II" (Fig. 183),

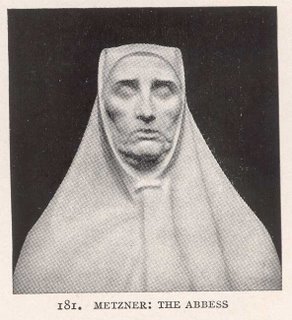

very striking in its massive simplicity; but most interesting of all is the remarkable head entitled "The Abbess" (Fig. 181), an unusually fine work which any sculptor might wish to have done.

This is reminding me a lot of Mestrovic --- and maybe Metzger would be just as well known in America if he had also come here

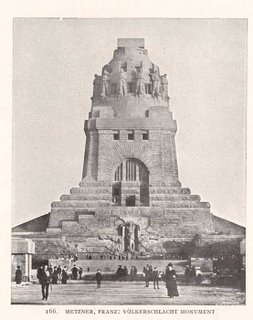

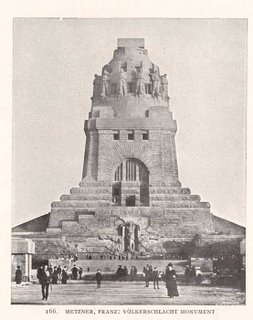

On the outskirts of Leipzig was dedicated in 1912- what is perhaps the biggest and most expensive military memorial in the world. Its very bulk makes it strangely imposing. It is known as the "Volkerschlacht Monument" (Fig. 166)

and commemorates German triumphs in the great battle of October, 1813, between Napoleon and the allied forces of Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Our illustrations give some idea of the size and design of this frowning pile. Of it a prominent architect remarked to me in 1913 that it was the most complete embodiment of brute force-of the power and will to crush ---that architecture has afforded since the pyramids. Nowhere on this earth, said he , can one find a structure which speaks so harshly, so inexorably, the language of ruthless might." In the light of recent events it must be counted one of the great monuments of the world, so triumphantly does it proclaim what it was intended to express!

I like this sarcasm -- cutting as it does both German militarism and the importance of artistic intention,

The monument itself looks truly monstrous -- like a toy castle that's been scaled up a million times. I can't believe someone ever saw a proposed sketch of it and said "Yes -- that's exactly what I want"

Volkerschlacht Monument: perhaps you could make it over into something else entirely, in the manner of swords into ploughshares. A very grand pigeon coop, perhaps. I’d also like to explore the crypt, though: weird little (big, I suppose: “cavernous depths”) spot for a daydream. The Metzner figures don’t look strange to me; you’re right, they have ancient MesoAmerican cousins.--Marly

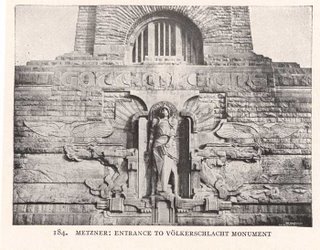

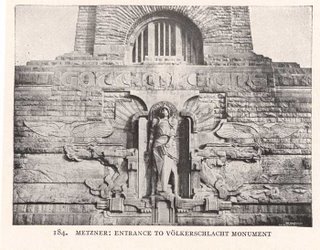

"The decorative pattern which covers the front is a colossal relief (Fig. 184),

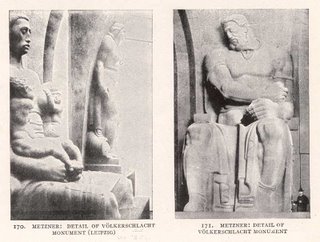

compounded of many unfamiliar elements evidently gleaned in oriental fields but harmoniously united and culminating in a giant figure of .Saint George. The skyline of the cupola, three hundred feet from_the ground, is ringed with twelve warrior figures, massive and unyielding-a superbly appropriate crowning feature. These, like the other enormous sculptures within and without, are by Metzner. Those inside the cavernous depths of the monument are so big and so mysterious that they require an entirely new standard of appreciation (Figs. 170, 171, and 185).

"require an entirely new standard of appreciation"?? That sounds like contemporary-art talk.

If only this were just a movie-set in the next episode of Indiana Jones -- so the whole place could be dynamited at the very end

You would hardly call them beautiful, at least not in any familiar sense of the word; but they cannot be overlooked. The writer has seen only the small models from which our photographs were made. The shadowy forms of the full-grown monsters are said to be wonderfully impressive.

It is a strange peculiarity of modern German sculpture that most of the mothers have twins! I suppose it is the decorative balance that the sculptors are seeking, but the result is monotonous and finally stupid. One can imagine how exasperating it must be to the race~suicide inclinations of the French!

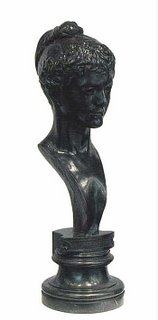

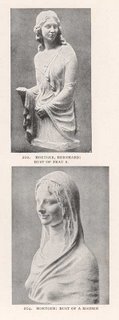

On the occasion of a visit to Germany in 1912 the writer desired to meet Professor Metzner and to talk with him of his extraordinary work. His exhibits, however, as then seen in Dresden and elsewhere, made the effort inadvisable, not to say impossible. How can you talk with a man who does things like this "Bust of a Lady" (Fig. 186)?

He seems to have fallen under some weird oriental influence, or else his "lady friend" is' a most extraordinary creature. The work certainly shows "mass” but all other sculptural qualities have fled.

Maybe I've become acclimated to German expressionism or ancient central America, but I don't have such a problem with this piece. She looks like one of those primordial earth goddesses , overshadowed but never overcome by the warrior gods of the sky.

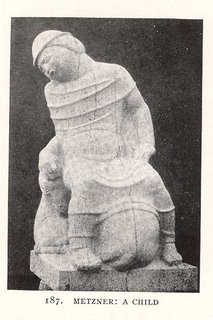

Another example of the new order where everything seems to be sacrificed to the massgefuhl, as the Germans call it, is entitled "Sorrow Burdened" (Fig. 188).

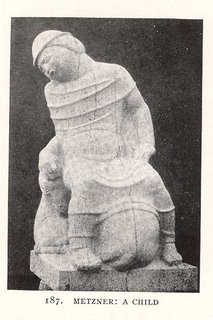

This so-called "Child" (Fig. 187) is of the same brood and is evidently" born to trouble as the sparks fly upward."

It has, however, a durable look, which is a sculptural virtue and prepares it for the worst. A "Seated Woman" (Fig 189)

is yet another of these amazing fantasies with which Metzner entertains himself and his public. In "The Dance" (Fig. 190)

we have as absurd an excursion as he has made, although the companion musician (Fig. 191)

is sculpturally enough conceived, In the Stelzhamer Memorial (Fig, 192)

I'm afraid "sculpturally conceived" means "more naturalistic" --- more like a real human body

he becomes sufficiently serious, and the characterization is pronounced, although the giant effigy is strongly suggestive of your Uncle Samuel. Another funereal monument is the Seiler Tomb, which is novel and yet dignified.

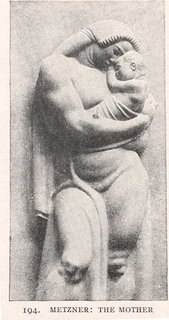

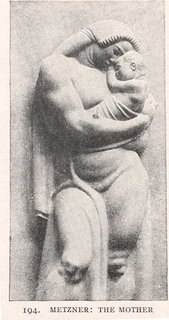

If I seem to give undue space to the often grotesque and enigmatic art of Professor Metzner it is for the reason that he is a commanding and a characteristic figure in German sculpture. His once distinctive traits are no longer his alone; half the young sculptors of Germany are trying to imitate him, while he has his choice of the most important commissions. Let us close our review of his work with this latest ideal of his, "The Mother" (Fig. 194).

How a man of genius can bring himself to perpetuate such ugliness it is hard to conceive. How his skilled hands can consent to such crudities is inexplicable. Fortunately all have not the same tastes. There is room for every kind of ideal in the world of art. The balance is restored by men like Karl Wilfert (1847-1916), who seems to have no affinity with the "fleshly school." This chaste figure is supposed to exemplify "Sensitivity" (Fig 195).

I prefer his monument to Adalbert Stifter -- which I'd call great cemetery art

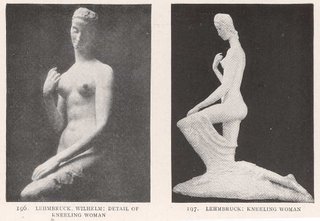

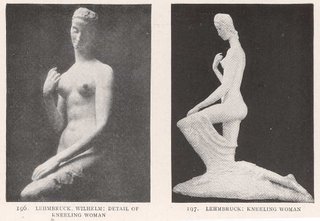

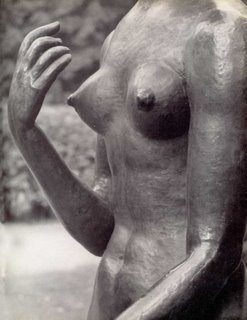

Another example of the lengths to which the up-to-date sculptors go is shown in a figure by Lehmbruck (Figs. 196 and 197).

It is not lacking in a certain kind of grace suggestive of Gothic decoration-but it is difficult to treat such work seriously even when it reveals, as here, the skill of the trained sculptor. Indeed such perversion of ability makes the crime unpardonable.

I guess we agree about the "grace suggestive of Gothic decoration" -- but where's the "perversion of ability" ? It certainly isn't self evident to me -- I love these pieces and have seen them in person. I guess they just don't fit Taft's vision of woman

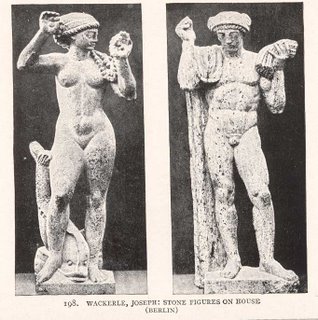

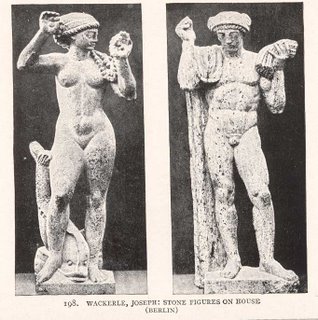

A favorite material for architectural decoration is travertine, a porous stone which hardens upon exposure. Composed largely of shells, it offers a worm-eaten surface giving the look of age to the newest creations. Let me introduce to you a happy pair of the archaistic figures which of late have been all the fashion in Germany (Fig. 198).

These are by Josef Wackerle (1880-1959), one of their most popular and industrious young sculptors. Many of the new buildings are made interesting by means of startling apparitions of this character. Some of them are fairly abloom with decorously improper nudities-the human form so ingeniously conventionalized that it is out of the question to hold anyone responsible for its behavior! The Aeginetan smile of the women and the buttonhole eyes and pneumatic-tire bodies of the cherubs brighten one's pathway on every street. Wackerle sometimes makes frankly grotesque figures, as in the decorations of the "Haus Lustig." Another work by the same sculptor (Fig. 200) shows the range of his somewhat individual ideals of beauty, as well as the variety of materials used by these clever men.

Again --This time, Taft invokes "individual ideals of beauty" -- instead of calling the piece ugly -- but I have real doubts about Wackerle -- and the only thing I've liked so far is that man with a horse.

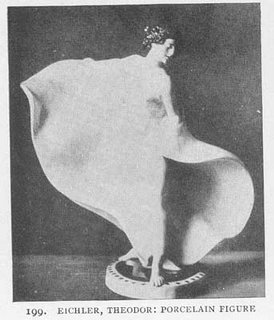

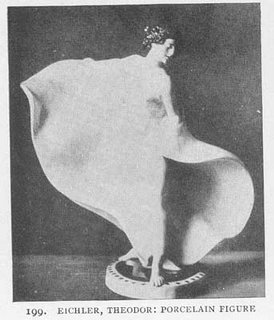

There has recently been a remarkable development of glazed sculpture in Germany and Austria--with results which would astonish the Della Robbias! Needless to say, the courtly traditions of Meissen and Dresden have been conscientiously forgotten by the young sculptors. No more grand-opera shepherdesses for them! Character studies, however, are ,not the only expression of the movement. This dancing figure by Theodore Eichler (Fig: 199)

gives a hint of the beautiful fancies and charming effects to which the miniature arts of faience lend themselves. There is no reason why these bits of "crockery" should not show all the essentials of great sculpture. It is only a question of good composition, of dominant line and harmonious light and shade- something just as possible in these little things as in a colossus. Especially in the use of animal and bird forms have many notable successes been attained. As in the wooden bears of Berne, the ultimate seems to have been reached; dexterity and intelligent simplification can scarcely go farther.

I think there's much more good "crockery" to be found -- like these pieces by Powolny that I recently stumbled upon. I suppose the genre has been demoted since it lacks a serious theme -- but that's never hurt the art reputation of all those delightful terra cotta figures from the Tang Dynasty.

Less appealing to our tastes, though appropriately reminiscent of the "land of porcelain," are certain fantasies by a very prolific sculptor of Darmstadt, Bernhard Hoetger. "Avarice" is pictured as a strangely contorted creature, while a very genial grotesque personifies "Light" (Fig. 203)

- so we are assured, although a superficial glance would pronounce the figure anything but "light." The pages of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration unfold an endless series of works by this happy and seemingly irresponsible artist. Indeed a whole book has been written about him, with illustrations of scores of his quaint fancies, many of which seem to be of a distinctly Gothic inspiration (Figs. 202 and 204).

I'm so grateful to Taft for introducing me to this great sculptor - confirming the adage that any publicity is good publicity in the imaginative arts. I've written about Hoetger here

I’d like to climb that visionary Hoetger staircase and walk down the Boettcherstrasse (on your link), too… He gives the feeling of someone rioting through art history as if through his very own playground.--Marly

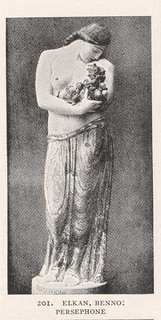

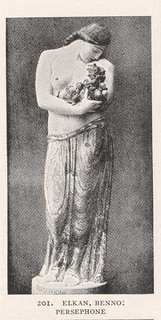

It is hard to realize that this astonishing chameleon of sculpture should have lived for ten years in Paris. He considers himself greatly beholden to Rodin and Maillol; one questions whether they would recognize their influence in his art. Of another character is the tinted figure "Persephone" by Benno Elkan (1877-1960) (Fig. 201),

first modeled for bronze but later elaborated in marble and other materials. It points to notable possibilities in decorative sculpture. If only we could do more enthusiastic and audacious experimenting in this line, what interesting results might be reached in the beautifying of homes!

Having made liturgical sculpture for the Israeli Knesset, it looks like Elkan is the most important Jewish-theme figure sculptor of his time.

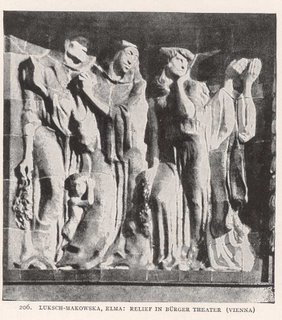

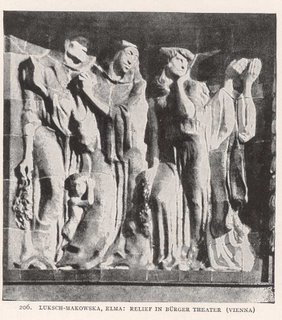

Nothing could more vividly mark the changes of a half-century in public taste than a comparison of the decorations of two theaters in Vienna. In Figure 205

we have an example of Viennese art of the middle nineteenth century . This florid frieze is a work of amazing virtuosity, but today it seems as absurd as the con temporaneous chignons and crinolines. A recent frieze in ceramic by the sculptor Luksch-Makowska offers a notable contrast (Fig. 206).

But isn't absurdity appropriate in the decoration of a theatre - where nothing is real and the make-believe changes every few weeks ? I think I might like Von Weye -- but there is zero about him on the internet

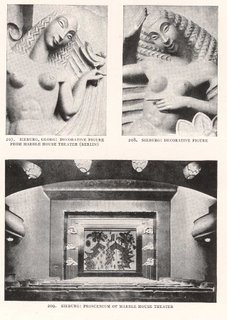

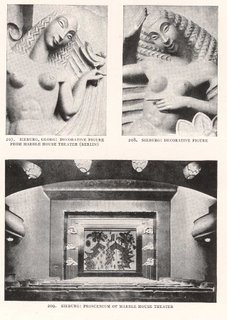

It is architectural in conception and keeps its place with a severe decorum undreamed of by designers a generation back. Fcuerhahn has given us likewise some admirable work on the same lines--or should one say "planes"? Even simplification may be pushed too far, however; George Sieburg's decorations for the Marble Theater in Berlin (Figs. 207, 208, and 209)

look as if made of creased tin or washboard material. Undoubtedly effective in their spotting, since grateful blank spaces are left between them, they are not of interest as sculpture. Maybe they are part of the white man's burden: examples of perverted oriental art. Let us call them "symptomatic "-having to do with what was the matter with Germany!

Nothing about Sieburg on the internet -- and I don't see how stands above the typical -- and cheesy --- art-deco found in older Midwestern movie theatres.

A rather absent-minded lady by Hermann Haller (Fig. 211)

is of the race which now embellishes all gardens and villas of the new Germany. It is this particular rendering which is the vogue, and "no other need apply."

Having touched on everyone he is feels is important - Taft is now finishing off with everyone else who deserves mention -- and I'm seeing quite a variety -- with the above as my favorite -- not because "you feel the stone" -- but because I feel a person -- not as she's pretending to be (Salome, art model, cheesecake, or whatever) --but as she is. So I'd like her in my garden, too

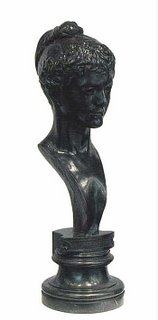

At first one finds it crude and disquieting; it seems so summary, so neglected. But it has one great quality; it is at the antipodes of realism. You feel the stone in the work, and presently in the products of the better men- you discover a sapient simplification, a suggestiveness that is refreshing. Take, for instance; the "Salome" by Hubert Kowarik (Fig. 213)

-how truly sculptural is the treatment, how austerely reticent even while it offers all of the essentials of the theme! Another " Salome" most decoratively conceived is by Hans Damman (1867-1942), of Berlin (Fig. 210).

I have never seen anything else from his hand, but hope to.

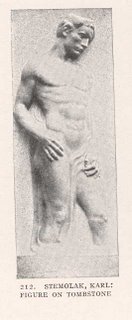

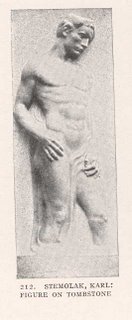

You will find no less admirable this tombstone (Fig. 212) by Karl Stemolak.

The anatomy has been simplified and reduced to its lowest terms, but it is there and is wonderfully "right"-an epitome of the human figure admirably expressed in the legitimate language of sculpture.

A very strange and yet appealing work is the "Stone of Lamentation" at Wickrath (Rhine Province) (Fig. 214),

a monument by Benno Elkan, whose "Persephone" has already been. mentioned. It is a large block surrounded by mourning figures in various postures of grief; not extravagant in pose but spiritually related to the groups on Bartholome's great work in Pere Lachaise. It would not be an inappropriate motif for a colossal "Chapelle Expiatoire," to be erected some day by a nation which has brought to the world as well as to itself more unnecessary sorrow and suffering than was ever known before.

Here's a 1940 Time Magazine story about Elkan, suggesting that this piece has been destroyed - and this might be catalog of all the rest of his lost work -- one more example of which follows:

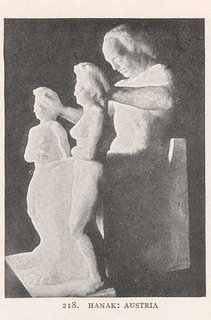

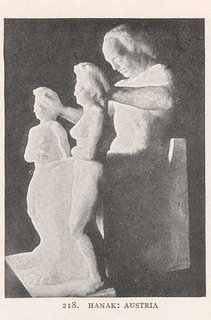

As has already been suggested, even so admirable a quality as simplification may be overdone. To reduce a figure to the shape of a brickbat or a half-used bar of soap may seem thrillingly original to the sculptor, but it asks too much of the good will of the observer. There are scores of men in Germany and Austria who come as near this as they dare. Hanak, for instance, a sculptor of Vienna, who is revered in Die Kunst and other magazines as though he were a second Phidias, turns out formless dummies like those shown in the group which he calls "Austria" (Fig. 218).

Perhaps it was a correct representation; if so, it helps to explain recent occurrences and our pity is awakened.

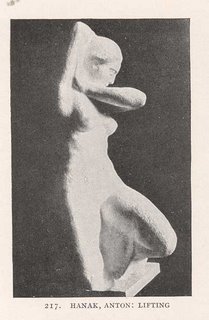

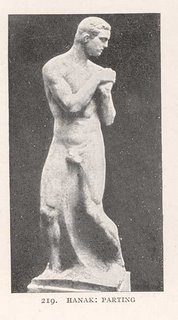

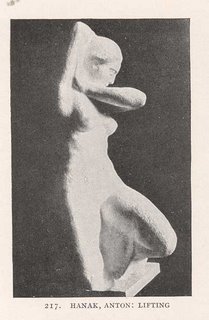

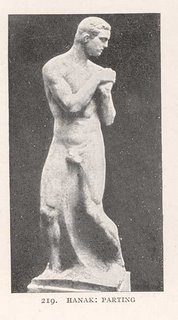

A large room was devoted to this modern master in the Dresden exhibition of 1912, and nothing in it was further developed than these giant sketches of action variously labeled "Lifting" (Fig. 217), "Parting" (Fig. 219), etc.

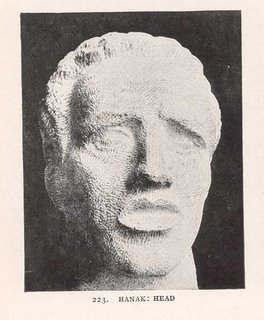

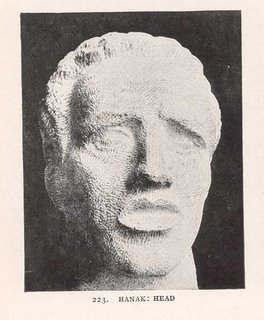

The figures are not badly proportioned and seem well started, but they are only begun, and one asks why they are cast and exposed before they have been studied. A head like this monster (Fig. 223)

is not interesting from any point of view. It has not even the interest of good construction; it is merely mussy. There is something weird and extraordinary in the composition which the sculptor calls "Das Kind fiber dem Alltag" (Fig. 220).

One has no idea what it is all about, but it does fix itself in memory!

This is the same criteria that I've begun to use: forget what it's "all about" ---- if your mind can't forget it -- it's good

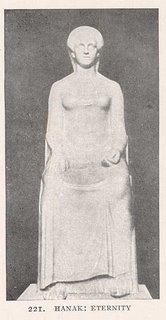

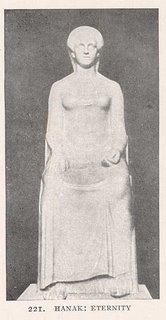

A more impressive work is the seated figure called "Eternity" (Fig. 221), a type which seems to be a great favorite just now with the Teutons; but Hanak has shown one great oversight: he has forgotten the twins!

Ouch ! I'm kind of a fan of Hanak -- and the piece Taft likes is one that I don't - because I'm thinking of Hanak as a kind of Zen painter -- whose statues come very close to being formless disasters --but don't cross that line - which I think is a frequent -- and maybe even admirable -- condition among those who successfully live in the modern, urban world.

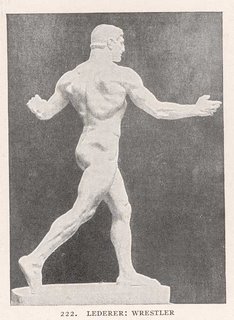

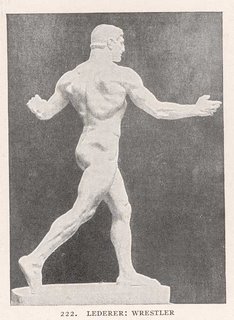

While in Berlin it was my privilege to visit the studio of Lederer, the sculptor of the great Bismarck Memorial at Hamburg. We found him engaged upon a figure so like the one just mentioned that it might well be the same, but in this case the babies were not overlooked. They were exactly alike in feature and pose. What it was supposed to symbolize I have long since forgotten. Herr Lederer showed us also a vigorous "Wrestler" (Fig. 222)

just completed, and a very able portrait of Richard Strauss, a bust of most convincing worth (Fig. 224).

I like these pieces by Lederer - especially the portrait -- and I also like the wrestler -- indeed, I like to look at all wrestlers -- but mostly for the suggestion of vulnerability, not just strength

Altogether I feel that this quiet modest little man is one of the great sculptors of our time. His Krupp Memorial at Essen is a work of much distinction; its ironworkers are par1ticularly noteworthy, while its felicitous combination of sculpture and architecture merits respectful study. Lederer has concentrated his great skill once again upon a representation of Bismarck (Fig. 165).

In this successful competitive model for a proposed statue at Bingen he conceived an amazing presentment of the founder and guardian of the German empire. Even in the small model the figure has the effect of colossal size.

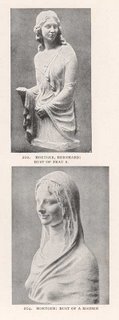

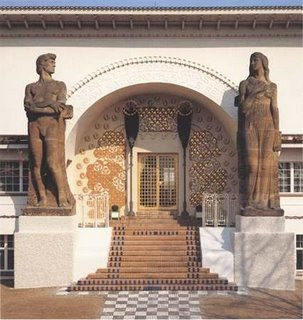

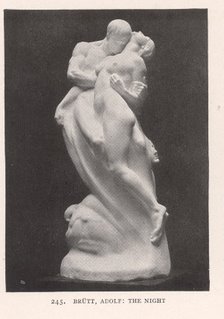

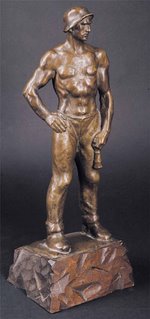

Ludwig Habich (1872-1949), a native of Darmstadt, modeled in 1901 the two handsome figures (Figs; 225 and 226)

which decorated the portal of the first exhibition held by the artist colony of that city. He has never surpassed this work of his youth.

I think I really like Habich -- and his "Columbus" is the best version I can remember. He was the right age -- with the right skills -- to be a successful Nazi sculptor -- so there must be some story -- possibly to his credit -- as to why he wasn't. I hope that much more of his work eventually appears on the internet

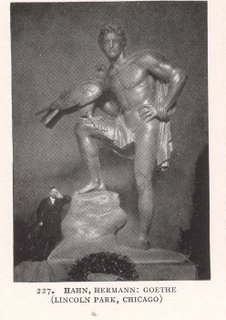

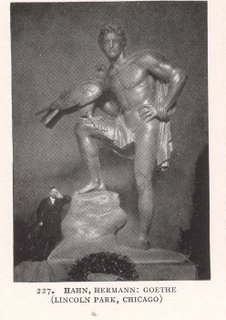

Another maker of monuments is Hermann Hahn, of Munich, whose Goethe Memorial in Chicago (Fig. 227) has caused so much discussion.

(photo taken from here)

(photo taken from here)

I'm guessing that this "discussion" was mostly critical -- as this piece feels badly overblown. My father once dismissed it as "academic" -- and it does seem to be like so much of the work found in "Sculpture Review": done by those who are intelligent, meticulous, and hard-working -- but without the blessing of the muse. But it might have been criticized just for being so silly -- transforming a Weimar intellectual into a powerful nordic god who looks like he could have been a professional wrestler, something like "Georgeous George"

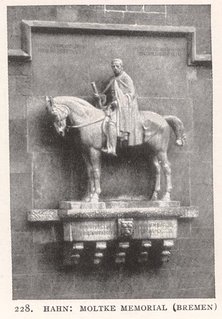

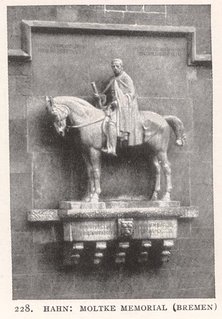

A more assured success is his equestrian "Moltke" in Bremen (Fig. 228).

I fail to see how this one is any better

Attached to an ancient church wall, where it seems to have grown centuries ago, it is an example of architectural fitness.

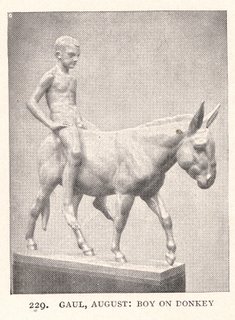

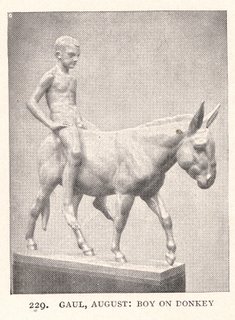

I find no sculptor of animals in Germany quite equal to August Gaul. His "Boy on Donkey" (Fig. 229)

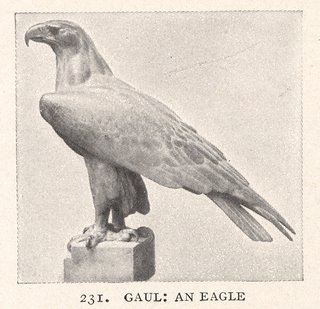

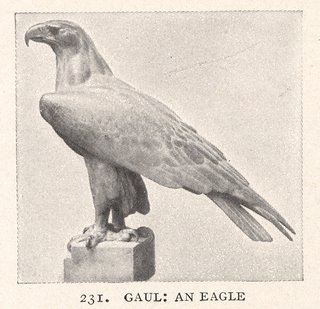

gives abundant evidence of his craftsmanship, but more original and personal are his "Penguin Fountain," his conventionalized "Eagle" (Fig. 231),

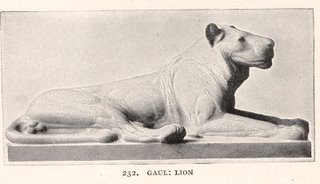

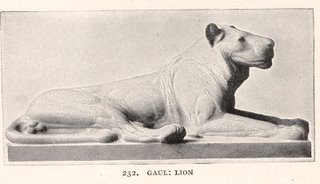

and his admirably drawn archaic "Lion" (Fig. 232).

It turns out that August Gaul might be the most popular sculptor in this essay -- with a hot market for framed photos of his animals -- and I think he was quite a sculptor of animals -- not with the ferocious naturalism of the great Barye -- but with the stately power of archaic sculpture (as Taft notes above) This is a man who looks at ancient middle-eastern sculpture as often as he goes to the zoo.

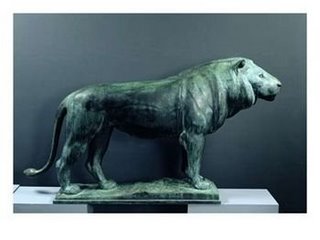

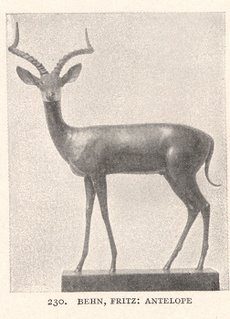

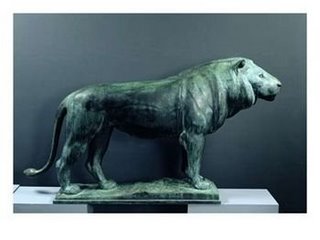

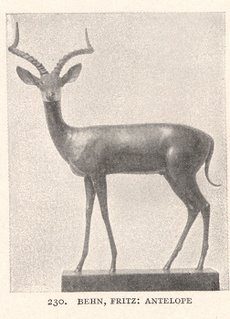

In this connection one cannot overlook the skilfully arbitrary renderings of animal life by Fritz Behn (1878-1970), of Munich (Fig. 230.)

Behn's treatment of the antelope is just a little more naturalistic than I'd like -- but his cemetery memorial below is no-holds-barred medieval German expressionism

As might be expected, the Germans practice wood carving more enthusiastically than do the French. Their exhibitions are always abundantly supplied with works in "Birnbaum" and similar woods. Here, for instance, we have a strangely passive young girl carved by Hermann Haller (1880-1950) (Fig. 234).

This is the same sculptor who made the "Absent Minded lady" (Fig. 211) shown earlier -- and I really like him -- and yet again -- have only to thank Lorado Taft for showing him to me. There's a museum for him in Zurich - and I'm hoping that a lot more of him can be found in books or on the web.

I love this guy -- and BTW -- his stuff is cheap -- the original terracotta shown above now going for $1600

A "Madonna " and a "Shepherd Boy" (Fig. 233) by Richard Langer(1879-1928) show an almost medieval character,

I hope, someday, to find more pictures for Richard Langer

while Franz Barwig's (1868-1931) "Wanderers" are appropriately set forth with an irreducible minimum of effort!

Barwig

Barwig

Barwig

Barwig

Barwig

Barwig

Barwig is apparently mostly known for his animals -- but I like his figures -- which appear to be miniatures -- and very effective -- reminding me of a mininiaturist from the next generation, Rene Sintenis. I wish someone would make a website just for miniatures

Some work in hammered copper for distant effects, two tinny saints by Professor Luksch (1872-1936), of the Hamburg Kunstgewerbe, attracted my attention. A head, the "Song of Labor," by the same artist was striking in its simplicity of modeling.

Luksch

Luksch

Luksch

Luksch

And I wish I could find more Luksch. He and his wife were also painters

Lingering amid the technical phases of the sculptor's art, let me pay my respects to that master marble-cutter, Theodor Georgii (1883-1963), of Munich. His "Entombment" (Fig. 235) has in it much of the great inspiration of the Renaissance, while his "Figure with a Net," carved without preliminary study directly in the stone, is a marvel. Georgii is also a recognized leader in animal sculpture. His small bronzes are worthy of the highest praise.

Georgii, 1948

Georgii, 1948

I first read this name in the Kineton Parkes book about stone carvers -- and Parkes praised him to the skies.

As I recall, he was closely associated with Hildebrand -- and hence the architectonic quality that Taft remembers from the Renaissance -- as well as a preference for relief.

And again -- I wish I could find more pictures -- especially some made within the past 80 years

I couldn't find any of Georgii's animals on the net.

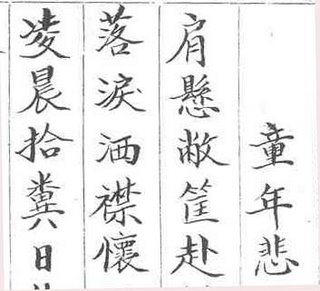

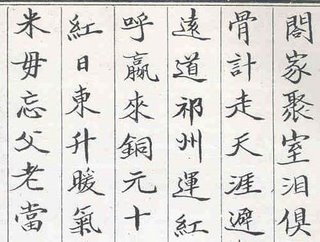

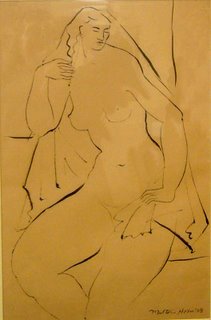

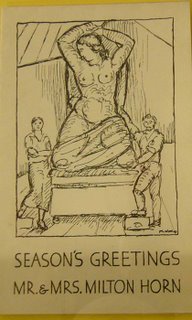

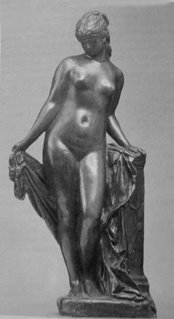

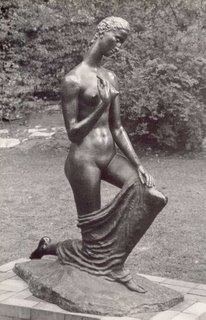

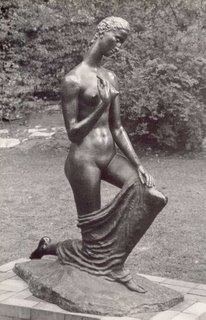

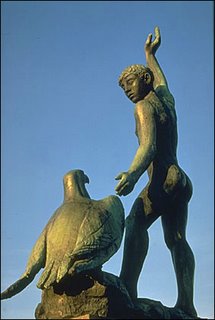

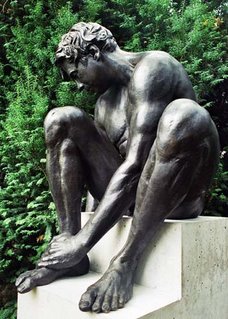

I have reserved until now one of the most conspicuous of the younger men. His name is Georg Kolbe , and you will find his slender, sinuous figures in every German exhibition and pictured in every magazine (Figs. 236-39).

Kolbe was an illustrator and painter before he turned to sculpture, and his work always shows gratifying draftsmanship. The female half-figure and her kneeling companion, "The Awakening," cut in sandstone for garden decorations are particularly attractive.

Kolbe is probably the first 20th C. German sculptor that I saw -- about 30 years ago -- because, of course, he's the only one, other than Lehmbruch, who's featured in American museums and art books. I liked him them -- I like him now -- and he is so prolific. It seems that he was even prominent back in Taft's day.

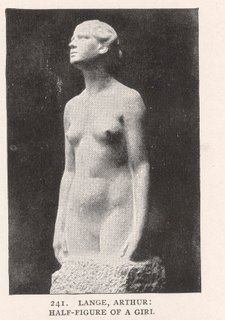

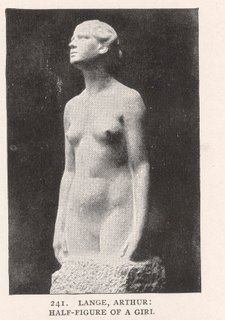

Arthur Lange, of Dresden, has produced charming figures of the same sort. It is hard to believe that a certain dainty torso (Fig. 241)

Many of these lesser-known German scultors can now be found on German Wikipedia -- but not Arthur Lange -- for whom there seems to be absolutely no reference except in Taft's book. Thankyou, again, Lorado

This piece feels like both a sculpture -- and a real person -- and that's what I find so thrilling.

is from the same hand that produced the brutal "Fountain of Strength," a group of massive athletes of such exaggerated bulk that they quite overdo their part.

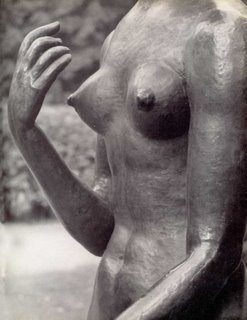

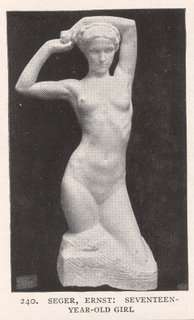

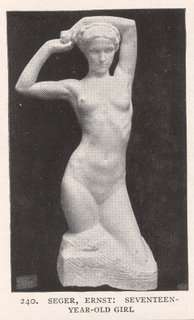

Yet another of these fine half-figures is by Ernst Seger (1868-1939) (Fig. 240)

and was among the choicest things which.I saw in a show of current works in Berlin. Our photograph was taken in a severely cutting light which makes the details seem rather insistent. In the softened light of the hall this was toned down without being formless; the lovely body seemed to float in an atmosphere of its own.

And this is why every art-book should be written by an aesthete like Lorado

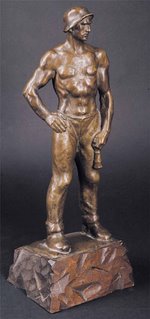

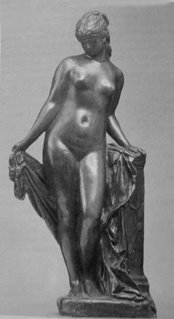

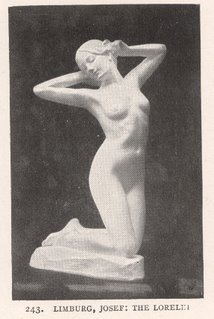

A "Lorelei" (Fig. 243) by Josef Limburg (1874-1955) had much the same charm. Limburg is--or was-a very young man, but he had already attined a remarkable craftsmanship when he modeled this figure. Despite its slender grace it is essentially sculptural in every respect. Even the narrow support has its distinct value in the composition.

I was going to say that this piece exemplified a typical studio pose -- rather than a human presence -- but by happy chance, somebody posted a recent picture of it on a German news site -- and now I can see why Taft enjoyed it so much - and even commented on how well it worked with its plinth

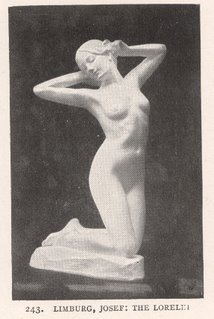

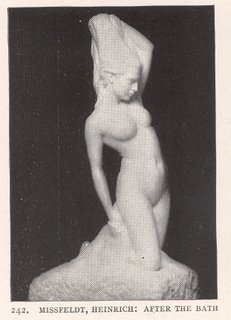

There is less of this subtlety in the figure "After the Bath " (Fig. 242) by Missfeldt (1872-1945),

What a fine monument he made to what appears to be a clinician. Any one of these obscure German sculptors of that era could step up and be the best American sculptor of our time

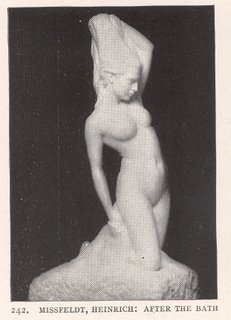

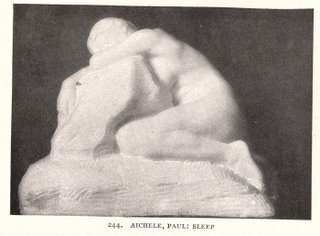

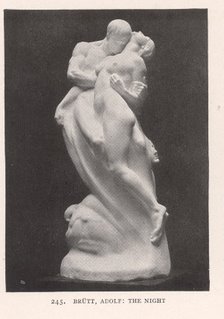

but the technique is essentially that of stone and most satisfactory. The group called "Night" (Fig. 245) by Adolf Brutt

Even German Wikipedia doesn't mention this guy -- and there's nothing from auction sites either -- but he looks like a very accomplished sculptor --this piece reminding me the one Taft has in the Art Institute.

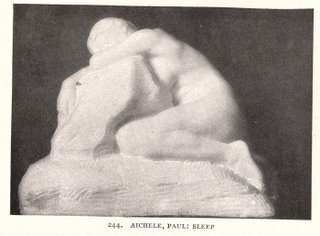

is one of the recent successes, while a companion theme, "Sleep," by Paul Aichele (1859-1910) (Fig. 244) is distinctly traceable to the "Danaide" by Rodin. Indeed Rodin's influence is seen in almost everyone of these later sculptures.

But such refinements are tame compared with the great bulk of architectural decoration. To succeed in Germany today one must produce things of a very different kind. Here is the ideal in its perfection. I offer you "Fruitfulness" by Karl Krikawa (Fig. 246);

in balance, in babies, in detail, in expression, this is absolutely the desire of all Deutschland!

I wonder why Lorado chose to end his lecture on a sarcastic note - I mean, the above piece is horrible (and the sculptor is now utterly unknown)

I guess his French taste has finally returned to him.

I look at these paroxysms and strivings for originality, and turning back to a certain bit of carved wood, sweet with the fragrance of forgotten centuries, I ask the "Virgin of Nuremburg" if we are really making any progress!

.

Christopher Smith

Christopher Smith Anthony Antonios

Anthony Antonios Judy Holder

Judy Holder Doris Buehler

Doris Buehler Michael Langlais

Michael Langlais