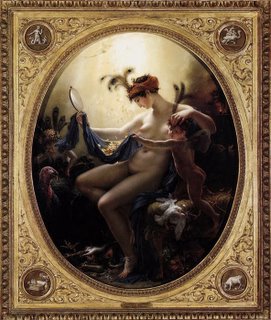

First week: I must have seen this guy back when I toured the Louve all those years ago - but when time is limited -- and Rubens. Poussin, and Delacroix beckon -- I didn't give him a moment's notice. Now though -- with a show all his own -- he's an oasis of splendor in the most threadbare of exhibition schedules the A.I.C. has ever had.

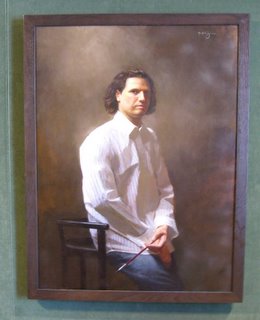

There's a self-portrait right at the beginning of the show that I might pick as his first and last great painting. He was 28 -- it was 1791 -- he was David's crack assistant breaking into his own career -- European history was being made on a day-to-day basis at the national assembly - and he portrays a young man who is sharp, keen, and hungry (much -- much more exciting than the later self-portrait in the Hermitage which is all over Google).

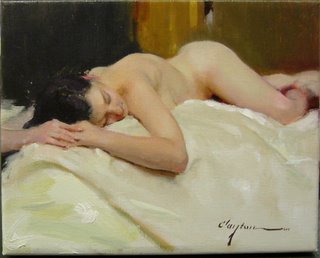

Of course he went on to make many great paintings -- he was a master of space, form, and color -- but he was not a prophet. He mirrored the taste of the rising bourgeoise -- seeking the shallow comfort of gorgeous but petty sensuality that at least never sunk to the sentimentality of Bouguereau and the later academy -- and that deserves to be called decorative -- but what decorations ! I can't imagine living a room surrounded by his life-size figures -- it would be so electric, I would never be relaxed.

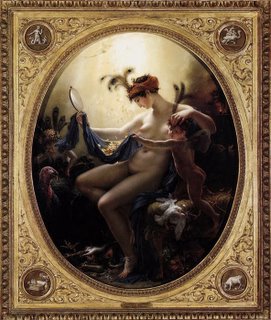

The piece shown above was at the show -- and, though thorougly delightful (far more so in person) -- shows the pettiness of his concerns. The lady depicted as Danae was a customer who had rejected his portrait of her -- so he painted her as a goldigger -- her husband as the turkey -- and somewhere in all the detail, a portrait of her lover. The lady was scandalized by society and the painter had his revenge -- but what a cheap use of his great talents.

This is a detail of a very large (and early) painting (which follows) -- showing among all those leaves, I hope, his powerful sense of space -- as well as a hommage to the great master of large-scale dramatic painting: Tintoretto.

There were many more great paintings which I couldn't find on the internet -- but they really have to be seen full-size to get the effect.

Given his abilities - and his frivolous nature -- my greated regret is that he didn't make explicit pornography. I think he could have rivaled the Japanese.

................Second Visit.............

Here's the self-portrait mentioned above -- something about how the facial features line up with how the space is proportioned -- something about the red lips -- and there you have it -- the integrity, the courage, the passion, the drama of a young man.

The first paintings I noticed this time around were the classical historical tableaux -- spinning off from David's "Death of Socrates" or "Oath of the Horatii" -- but almost immediately, it's apparent that the timeless, heroic, serious Classical detachment is gone -- and instead, we're getting some kind of elaborate cartoon -- with grimacing faces that forget they're actors on a Classical stage. (detail of "Joseph and his Brothers" shown above -- and doesn't look like a scene from the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical ?)

Girodet may be the greatest French painter between David and Gericault/Delacroix -- but in comparison with them -- well --- let's just say he feels like a lightweight.

The next painting I noticed this time was the Ossian fantasy he painted for Napoleon (detail shown above) - and with the pretense of classicism gone -- the silliness is actually more enjoyable -- demonic British ghosts battling heroic French ghosts -- surrounded by beautiful ghostly young women, glowing with a supernatural light. It's like the best cover art that trashy pulp fiction has ever had. Napoleon, apparently, didn't like it -- but I think he lacked a sense of humor.

The last paintings that I saw on this visit were the portraits that he did of an older physician, Dr. Trioson, who cared for Girodet when he was a young orphan, and formally adopted him as an adult. I don't know the story behind their relationship -- but the physician is presented as a very kind, caring, rational, and level-headed man -- perhaps a foil to the artist's own whimsical, poetic nature. Actually -- on this visit -- this portrait was the painting that moved me the most. Girodet knows nothing about half-measures --and the character of that father figure jumps out of the frame.

The following is a link to an essay based on the 1911 entry in the Encyclopedia Brittanica:

click hereYou'll notice that the painter is taken to task for trying to express Romantic sentiments within a Classical style -- but I don't know that I want to follow this progression-of-styles approach that is the foundation of academic art history. As I read the character of Girodet the orphan -- I think cherished a fantasy life that semed much more attractive than the cruel world -- and that's where he took his painting. If he were directing films today -- I'd see him as a Steven Spielberg -- and if making movies were an option back in 1800, I think he would have preferred that to painting.

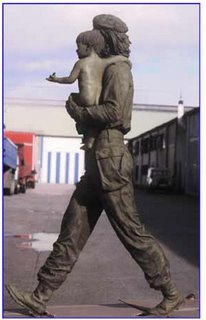

Not much for me from Nubia -- but isn't this pot rather elegant ?.

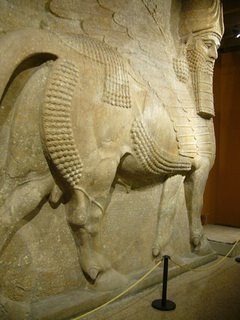

Not much for me from Nubia -- but isn't this pot rather elegant ?.  Here's the star of the collection -- custom made for Sargon II c. 720 BC in his short-lived capitol of Khorsabad. There are several other monumental relief panels from that palace -- but it appears to me that the master sculptor himself worked on this one -- designing all the others, but leaving assistants to complete them. The drama -- the presence -- the magic -- this is what sculpture is all about.

Here's the star of the collection -- custom made for Sargon II c. 720 BC in his short-lived capitol of Khorsabad. There are several other monumental relief panels from that palace -- but it appears to me that the master sculptor himself worked on this one -- designing all the others, but leaving assistants to complete them. The drama -- the presence -- the magic -- this is what sculpture is all about.

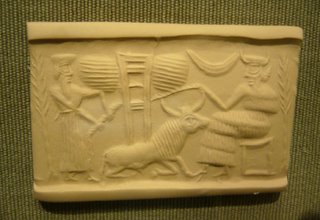

At the other end of the size scale -- come these one-inch

At the other end of the size scale -- come these one-inch I can't figure these things out -- but these don't seem to be church-going girls -- expecially the one with the very pert bottom. And what fell on that other girl's head ? Who knows. (they're both from Palestine - c 1200 BC - Good-for-nothing Canaanites, no doubt. )

I can't figure these things out -- but these don't seem to be church-going girls -- expecially the one with the very pert bottom. And what fell on that other girl's head ? Who knows. (they're both from Palestine - c 1200 BC - Good-for-nothing Canaanites, no doubt. ) But I think I know what this one is about.

But I think I know what this one is about.

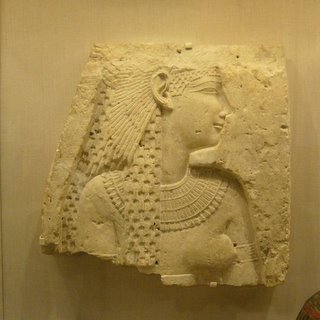

This goddess is very recent, as Egypt goes --

This goddess is very recent, as Egypt goes -- I forgot to record the origins of this one -- but I like sculpture of musicians --so here it is.

I forgot to record the origins of this one -- but I like sculpture of musicians --so here it is.  I'm really attracted to this very ancient and very cute couple. They seem so eager to please. Wouldn't you like to have had them as parents ? They're Old Dynasty -- about 2400 BC from the tomb of Nenkefetka

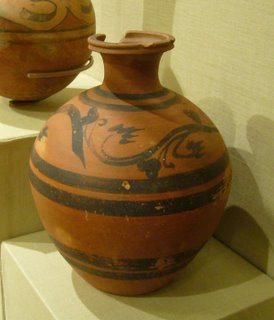

I'm really attracted to this very ancient and very cute couple. They seem so eager to please. Wouldn't you like to have had them as parents ? They're Old Dynasty -- about 2400 BC from the tomb of Nenkefetka There were two Persian bowls from Istakhar -- so I'm guessing they're from 4th c. BC.-- and they are ecstatically beautiful -- as their design spins off into another world. This is the civilization that Alexander destroyed.

There were two Persian bowls from Istakhar -- so I'm guessing they're from 4th c. BC.-- and they are ecstatically beautiful -- as their design spins off into another world. This is the civilization that Alexander destroyed. This is a Cypriot 'bilbil' jug found in Palestine from about 1300 BC.

This is a Cypriot 'bilbil' jug found in Palestine from about 1300 BC.