Modern Tendencies in Sculpture

Francois Rude

Francois RudeFollowing the esteemed Sir G's example, this is the post of a "guest blogger" -- in this case, the dean of Chicago sculptors, Lorado Taft (1860-1936)

In 1920, he published a set of lectures under the title of "Modern tendencies in sculpture" - and perhaps the fact that "modern" modifies "tendencies" instead of "sculpture" should warn the reader that this will not be a typical survey of modernism in the arts.

For me, it best serves as an introduction to the kind of sculpture that Taft liked best -- the kind that he emulated when he studied in Paris -- the kind that set the standard for his work and teaching.

Some of them are still famous -- and some have fallen into almost total obscurity.

When it came to providing picture examples in his book -- this section was only illustrated with the things he hated -- Matisse etc -- so I had to dig up pictures for the rest - where possible.

So ... sit back .. and let the old man give his lecture. He would have been about 60 at the time -- at the peak of his career -- as both a public sculptor and academic authority at the University of Chicago.

All the following words are his (my response will come in the comments that follow)

*****************************************************************

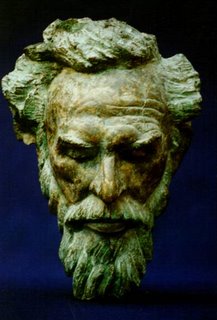

RECENT FRENCH SCULPTURE

The subject of our last causerie was Auguste Rodin. “Rodin and His Influence” had been the intended theme, but it soon.developed that there was so much to be said about Rodin and his work that the influence had to be left for another day. It will form a part of the inquiry of this chapter, as indeed it must run through all of these papers excepting the one devoted to Saint- Gaudens; I cannot find that the art of our great American sculptor was touched in the slightest degree by that of the French master.

Of course M. Rodin’s independent and very personal point of view has not been the only influence at work during these later years. Whatever the immediate trend of French sculpture, the dominant fact is the momentum of an age-long tradition. This tradition had, become in great measure academic; but, as Brownell wrote of the French school of twenty-five years ago, “It is a thoroughly legitimate and unaffected expression of national thought and feeling at the present time, at once splendid and simple.”

Every now and then through the years the current has been shaken and then reinforced by some powerful influence-“ an angel has troubled the waters.” In the the first half of the nineteenth century it was the towering “ personality of Rude; a little later it was Carpeaux then Dalou; then Rodin. The part that each of these men has played is clearly marked, although not yet complete. The stream of sculpture is tinged ever after by their contribution as distinctly as the Mississippi is colored from St. Louis onward by the waters of the Missouri.

To appreciate what Rodin did to it one must have a definite idea of what it was before. A few minutes of retrospect will be valuable. What has been the trend of sculpture in France? What the impress of these great artists upon its course? To go back no farther than the memory of men still alive, there is always the heroic figure of Rude beckoning to high achievement through his triumphant work on the Arc de Triomphe, “The Song of Departure.” (Pictured at the top)

Of this great relief it has been eloquently said:

“No one can have any appreciation of what sculpture is “Without perceiving that this magnificent group easily and serenely takes its rank among the masterpieces of sculpture of all time. It is, in the’ first place, the incarnation of an abstraction, the spirit of patriotism aroused to the highest pitch of warlike intensity and self-sacrifice, and in the second this abstract motive is expressed in the most elaborate and comprehensive completeness with a combined intricacy of detail and singleness of effect which must be the despair of any but a master in Sculpture.”

The Departure” has become a classic, but it is too exalted, too exceptional, to influence deeply the everyday output of Parisian studios. The graceful “Neapolitan Fisher Boy” and even the vehement “Marshal Ney” have been more obviously potent.

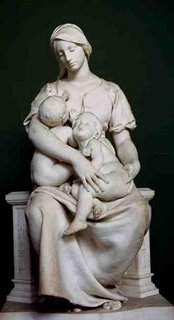

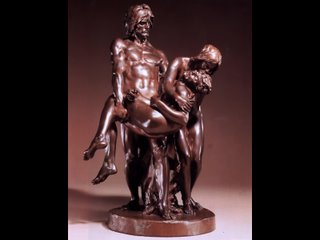

Rude’s immediate spiritual heritor was: his pupil) Carpeaux, whose feverish temperament drove him to an eternal quest of life and movement. With alluring charm and incredible skill he pushed his art to what seemed at the time absolute realism. In principle wrong, the manifestation was so seductive that against their better judgment the critics were silenced. At least, no one heeded thejr criticisms. In the face of these irresistible works they but wasted their ink and paper. Carpeaux left us treasures of passionate expression; it was the little, cold-blooded would-be Carpeaux’s of a second generation who have torn Parisian monumental art to shreds. One of Rodin’s fervid biographers tells us that the master’s “immediate forerunners recognized only one form of beauty, an insipid, affected, inanimate prettiness of which the renowned Bouguereau was the last successful representative in pictorial art.” This characterization might have applied to much of the sculpture of a hundred years ago but hardly to that of the second half of the nineteenth century. You may judge whether such terms describe the art of Carpeaux. Let us turn to a few more of the immediate forerunners of the master that we may” see how “ insipid, affected, and inanimate” they are. Look upon Paul Dubois’ “Charity” an achievement which even the wizardry of Rodin does not put in the shade.

Paul Dubois "Charity"

Paul Dubois "Charity" Paul Dubois "Military Courage"

Paul Dubois "Military Courage"View his “Military Courage” and the exquisitely tender figure of” Faith.” Consider the vivid and truly sculptural conception of ” Joan of Arc” by Chapu.

Chapu "Joan of Arc"

Chapu "Joan of Arc"Study “The First Funeral” by Barrias) once recognized as the masterpiece of modern French sculpture.

Barrias "First Funeral"

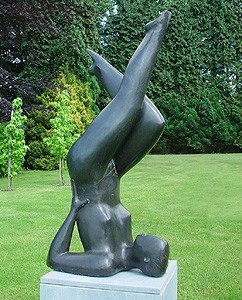

Barrias "First Funeral"What of inanimate prettiness does one find in Saint Marceaux' "Genius of Death"?

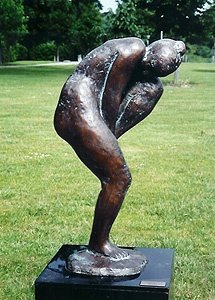

Saint-Marceaux

Saint-MarceauxOther favorites of forty years ago were the rugged "Age of Iron" by Lanson, Aube's dramatic "Dante,"

Aube "Dante"

Aube "Dante"

and the sternly simple "Ancestor" by Massoule. Mercie's "Gloria Victis" holds secure sway amid remembered enthusiasms,

Mercie "Gloria Victis"

Mercie "Gloria Victis" Mercie "David D'Apres le Combat"

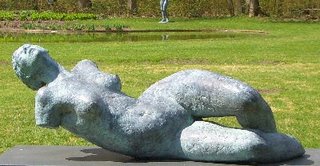

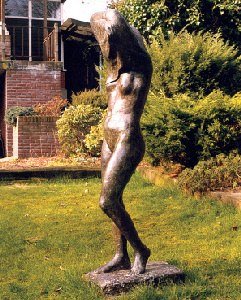

Mercie "David D'Apres le Combat"while one noble female form seems to float above them all-the radiant "Aurora" of Delaplanche.

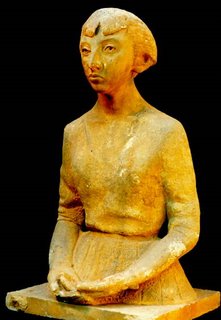

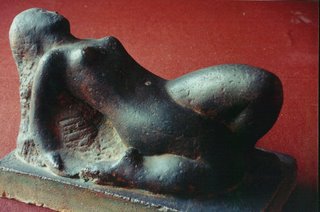

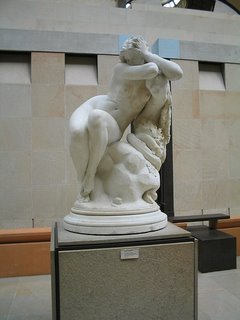

Delaplance ("Eve after the Fall")

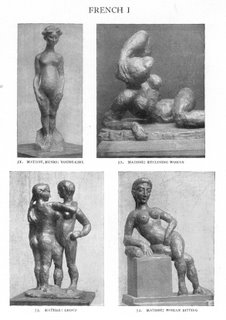

Delaplance ("Eve after the Fall")You can imagine the emotions of a wistful artist returning to the scene of these early loves to find them replaced by strange gods like this foolish caricature of a woman (Fig. 51). It is a work by the notorious painter, Matisse. You see he is quite as good a sculptor as he is painter! They tell us no female is so queer that she cannot find a companion, if she tries; it is gratifying to, observe that Matisse's ideal has an affinity (Fig. 53). No, a second look discovers that they are both of the same kind. Unfortunately these nondescripts do love and propagate; here is a chaste "Kiss" by Brancusi, (Fig. 62); and here is "Family Life" by Archipenko (Fig. 61). Brancusi was the author of the far-famed "Mile Pogany" (Fig. 59), which, we are assured, is "not a servile reproduction of features," but an interpretation of the soul. Perhaps its companion (Fig. 60) is Miss Pogany's sister's soul, although, it has been called "The Mislaid Egg."

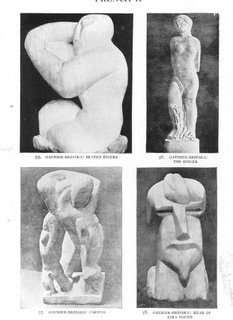

For mischief or through sheer imbecility many unsuccessful sculptors turned to this form of prostitution. One of these deluded youths was Gaudier-Brzeska, who was later killed in the trenches. An American poet wrote a eulogistic book about him and gravely presents his infantile products for our respectful consideration (figs. 55-58). We are unsmilingly assured that such objects show forth "the fundamental verities"; that "representation" is naive and childish, but that these geometrical forms are "the expression of a pure idea-the expression of the absolute."

Gaudier's "Seated Figure" (Fig. 55) recalls the impassioned description of a similar amorphous mass, words written by a hypnotized votary: "There is a swell of volume in all directions and which to a sensitive and patient attention produces a sense of freedom and a sense of power that comes out from within." No doubt a little patient and sensitive attention, would likewise discover "a flat submerged plasticity" of incalculable value. Another sentence from the same authority is so wonderful that it insists upon use as a high light in this drab essay of mine: "The whole is like a growth of nature and like within a single sweep of tight contours which enclose the greatest possible plasticity within the smallest compass." In the presence of such mysteries of thought and diction one can but bow and reverently withdraw.

Figures 51-54

Figures 51-54 Figures 55-58

Figures 55-58Footnote: The men who produced these last mentioned curiosities are presumably aliens in France, but their so-called art was incubated and brought forth in Paris througb the hospitality of a public which is ever seeking “some new thing.” The information obtainable in regard to their shadowy personalities is so slight and so contradictory that some have been tempted to believe them fictitious-a syndicate, or possibly a “Mr, Hyde” manifestation of some perfectly reputable artist. What sculptor has not cherished for a moment the wild wish to exhibit, under a pseudonym, the startling abortions or easily sketched grotesques which appear and disappear in the daily routine of the studio?