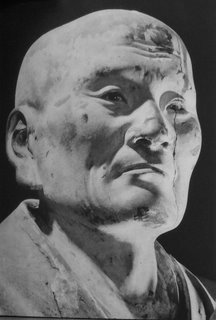

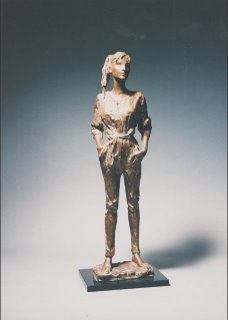

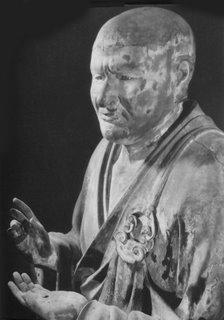

(Sogyo Hachiman (Shinto deity) in disguise as a Monk - 10th century)

The following essay was found on an antiques site -- and I've copied it to this blog because it seems to be very informative -- and nothing stays on the internet forever.

It's orgin - and the the author's name -- were not given -- nor, regrettfully, are all the photographs to which so many references are made. I'm sure that brief histories of Japanese sculpture are available from many printed sources -- but this one seems to be especially valuable since the author makes no effort to hide his taste -- so I'm thinking that his passion has been aesthetic as well as historical.

You will notice that Asakura Fumio is mentioned as a current instructor in the Imperial Academy of Fine Art -- and one of the other instructors died in 1942-- so it cannot have been written any later.

............................................................................

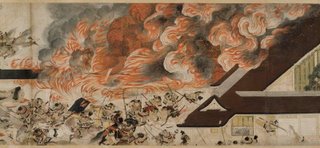

Haniwa horse, 250-600 AD

Before the introduction of Buddhism, in the middle of the 6th century, Japanese sculpture seems to have been quite simple and archaic in its material and technique. There remain only statuary objects stuck on burial-mounds built in the proto-historic period. They are crude terra-cotta figures, which is one of the examples preserved in the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum.

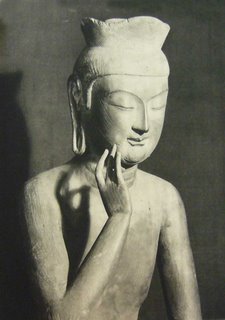

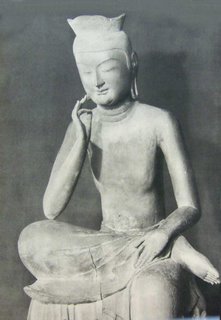

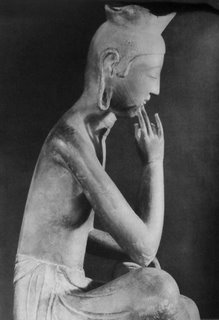

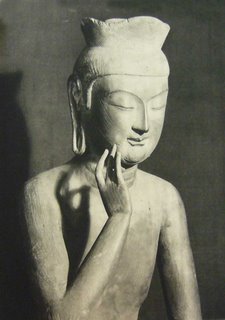

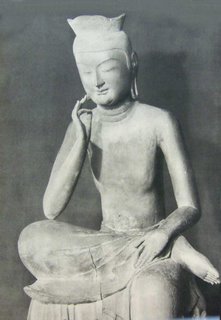

Bodhisattva in Hanka pose, Koryuji Monastery, 7th C.

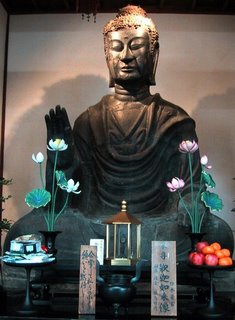

It seems that highly-developed Buddhist figures in bronze and wood were produced quite suddenly in the first half of the 7th century. Some representative examples of these early Buddhist figures still remain in the Horyü-ji monastery in Yamato. They were mostly produced in the reign of the Empress Suiko, because of which they are known by the name "Suiko sculpture." In the Suiko sculpture there are two styles ; one is the Tori style, and the other the Korean style. In the Golden Hall of the Horyu-ji monastery is enshrined the triad image of Shaka-muni Buddha which is made by the sculptor Tori (Fig. 28).

This is the most representative example of the Tori style sculpture. This triune figure is of cast bronze still bright with gold. It expresses archaic dignity, but its pose and lines are too stiff and over conventionalized. Technically, this figure shows the direct indebtedness to the Chinese North Wei stone sculpture. The best example of the Korean style of the Suiko sculpture will be seen in the wooden figure of Kwannon, also in the Golden Hall of the Horyu-ji.

It is extremely slender and tall, almost transcendental in form and height. When compared with the former example, this expresses much more delicacy and the curved rhythmic beauty of lines. The wooden figures of the Suiko sculpture were carved out of a single block of wood, and always decorated with colors or brightened with gold-foil.

In the second half of the 7th century there developed a new style of sculpture due to the influence of the Gupta style of Indian sculpture which was introduced into Japan through China. The style and form of this new school is very different from that of the Suiko sculpture, and it is known by the name " Hakuho sculpture." It has curves much fuller and more rounded, illustrating more human life. The bronze statue of Sho-kwannon (Fig. 30) in the Yakushi-ji monastery is an important example of this new style, produced in japan. Its posture is stern and majestic, and the form of body is realistic. The thin transparent drapery is so filmy that one may feel the pulsating warmth of the body. Such gracefulness is the most conspicuous feature of the Hakuho sculpture of the Hakuho era (645-709).

In the history of Japanese sculpture there were two golden ages. The first in the 8th century, which is known by the name " Tempyo sculpture," and the second is the " Kamakura sculpture " in the 13th century. In the first golden age a striking development was made with new media of clay and dry-lacquer under the influence of the T'ang sculpture of China. In these media almost perfect beauty of human form was visualized with spiritual dignity. There still remain a number of such masterpieces in some monasteries in Nara and its vicinity.

In the Hokke-do (Sangwatsu-do) chapel of Todai-ji are two figures representing Nikko and Gwakko, which stand on either side of the main figure of the chapel. Both are representative masterpieces made of clay in the 8th century. Their planes, lines and volumes are beautifully formed by fine clay merely hardened with drying, assuming a beautiful silvery gray color. The well-rounded and quiet classical repose ex-presses inner spirituality. The refined dignity of the divine face, which is miraculously combined with human beauty, is not surpassed by any other statue in the world (Fig. 31). Indeed, in this piece the plastic genius of Nara sculptors is most skilfully carried out. A number of examples of other masterpieces in clay will be found in the Nara Imperial Household Museum, the Kaidan-in chapel at Nara and in the Horyuji monastery near Nara.

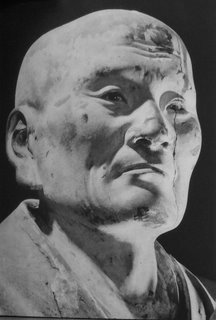

In the sculpture of dry-lacquer statue, different methods were used. However, the most practical of all the methods was the so-called " hollow statue" process, in which a model of clay was made and covered with lacquered cloth. When both the clay and lacquer had hardened, the inside of the figure was dug out, leaving a hard shell, which would neither warp nor split. On the surface thus obtained were elaborated all the details of the statue by lacquer mixed with makko or powdered incense wood. Excellent examples in dry-lacquer may be seen in the Nara Imperial Household Museum. Among them are four of the ten great disciples of the Buddha Shaka-muni which are owned by the Kofuku-ji monastery. They are successful in representing individual personality, as will be seen in the one reproduced in Fig. 32.

In the Hokke-do chapel at Nara, and the Toshodai-ji and the Shorin-ji monasteries near Nara, will also be found some masterpieces of dry-lacquer work.

In the 9th century a notable development was made in wooden sculpture, and the clay and dry-lacquer, which were very popular with the Tempyo sculptors, declined and finally died out. Those wooden statues produced in the 9th century are lofty, sublime and inspiring ; and in their technical finish there are two kinds. One is embellished with colors on gesso ground or laid over with gold leaf on lacquered ground. The wooden figure representing Nyoirin-Kwannon, which is enshrined in the Kwanshin-ji monastery in Kawachi, is an excellent example which was once adorned with colors, although they are now almost gone (Fig. 33). The work is marvelously successful in rendering his mystic power. It has grace of form and expression, and though it has six arms it does not give any impression of being grotesque.

Another kind is finished entirely in wood, and makes use of the color of wood to obtain a beautiful finish. The statue produced by this method is called dan-zo. One of the excellent examples of this technique is the Eleven-headed Kwannon enshrined in the Hokke-ji nunnery near Nara (Fig. 34). The figure is carved out of sandal-wood. The form of the body is excellent, and harmoniously blends with the noble beauty of the main face, while the carving of its folds of drapery is sharp and deep, admirably expressing the spirit of the age.

In the following three centuries, viz. 10th, 11th and 12th, the sculpture was somewhat eclipsed by the prosperity of painting. However, in its technique a new method developed in wooden sculpture which was usually carved out of one block of wood. The new method was a joinery structure. The head was carved separately and inserted in to a part of the neck ; the body was composed of three parts, and the hands and arms also were carved separately and then dove-tailed into the body.

Those statues produced in these three centuries are called " Fujiwara sculpture after the age known as the Fujiwara Period (or later Heian Period). The characteristic features of the Fujiwara sculpture are the round face, the delicacy of form and the picturesque ornamentation.

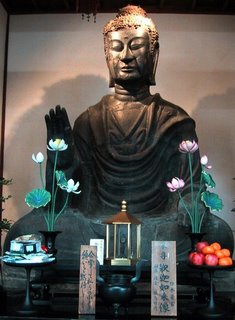

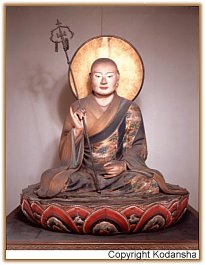

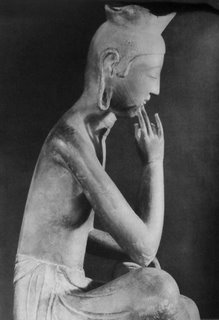

It was also noticeable that professional sculptors appeared for the first time in the 11th century. Among the fore-most was Jocho, who established a carving studio in Kyoto and there taught his pupils. AIthough they imitated his style, they could not surpass their master. The large image of Amida enshrined at the Ho-o-do, or Phoenix Hall of the Byodo-in at Uji, near Kyoto, is said to be a representative work carved by Jocho (Fig. 35).

It is made of wood and entirely overlaid with gold-foil. Buddha sits cross-legged on a lotus pedestal with his hands on his knees.

The most representative example of the picturesque statues produced in the 11th century, is the figure of Kichijo-ten, the deity who is the incarnation of beauty, from the Joruriji monastery, now preserved in the Tokyo Imperial House-hold Museum.

She holds on the palm of her hand a gem, which has a magic power to give fortune to her devotees. The chiseling is magnificent, and the costume is beautifully decorated in colors with typical designs of the age.

The advent of the second golden age of sculpture in the Kamakura Period seems due to the following four causes :-

1. The martial spirit of the age created by the new military administration and the attitude of sculptors responding to this spirit, was one of the four causes which brought about this golden age of sculpture.

2. The great demand for Buddhist figures owing to the reconstruction of the great monasteries at Nara and the erection of new Buddhist temples in Kyoto and Kamakura.

3. The unique opportunity the sculptors had in seeing a great number of masterpieces remaining in Nara from the Nara Period, the first golden age of sculpture.

4. The influence of Chinese statues and paintings of the Sung Dynasty which were characterized by realistic features.

There appeared two great master sculptors representing the Kamakura Period, Japan's second age of sculpture. They were Unkei and Kwaikei. Unkei, the son of Kökei, succeeded in expressing the new spirit of the age. He had great skill to interpret activity and courage. Even when his subject was placid, he tried to catch the intrinsic movement with a vital touch of his chisel. The two Nio or Deva Kings standing at the gate of the Todai-ji monastery in Nara show Unkei's genius at his best. They are the largest statues of Nio in Japan, having a height of 26.9 ft.

Their majestic features are well proportioned to their Herculean physique. They are indeed physically perfect and unequalled in the expression of terrifying fierceness. Although these two statues are attributed to Unkei and Kwaikei, they most typically represent the type and technique of Unkei. He was skilled also in portrait sculpture. The figure of Seshin, now placed on view in the Nara Imperial Household Museum, is a masterpiece by which his genius is shown in portrait sculpture (Fig. 38).

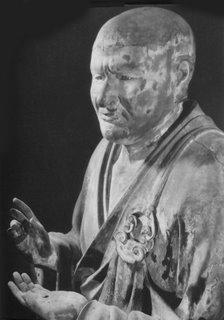

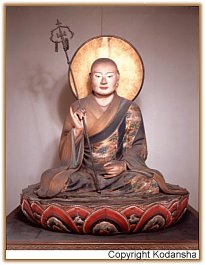

In this figure the individual character of the priest is wonder-fully visualized by his genius. The bold, forceful, and rhythmic folds of drapery chiselled out of a simple block of wood reveal a personality, grand not only in physique, but in spirit. Kwaikei, the great contemporary of Unkei, showed the new spirit by his embellishing of old forms. He was most skillful in representing peaceful subjects, such as Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, while Unkei showed his genius in rendering chivalrous subjects, as has been already explained.. The greatest of his works is the figure of Hachiman-Bodhisattva of the Todai-ji monastery in Nara (Fig. 39).

Its form and expression are full of reality, and there is nothing superhuman about it. It looks like an ordinary man with a calm and noble posture. But Kwaikei had almost no pupil who mastered his technique and style for the future, and Unkei had four sons, who all mastered their father's style and technique, and played an important role in the development of the Kamakura sculpture. The figure of Kongo-rikishi is an excellent example of the work attributed to Jokei, one of Unkei's sons. In this figure, we see the very spirit of the Kamakura sculpture, highly expressed by the active movement of its limbs and the sweep of the drapery which give a perfect rhythmic unity. This may now be seen in the Nara Imperial Household Museum.

Buddhist sculpture in Japan reached its highest development in the Kamakura Period. From then it continually de-clined, and never revived its supremacy.

Temple Guardian (Art Institute of Chicago)

However, masterpieces of portrait figures of high priests were produced in the Muromachi Period (1334—1573) which followed. This was because of the popularity of Zen Buddhism. It is also noticed that the carving of Noh masks made a new development owing to the popularity of the Noh drama among the feudal barons and aristocratic class.

In the Momoyama Period a unique development was made in architectural sculpture, which will be described elsewhere.

Coming down to the Edo Period, sculpture declined even more, except for small things such as masks, netsuke and so forth.

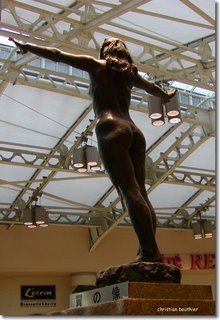

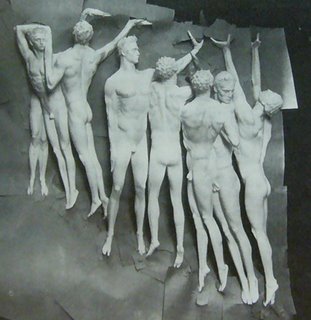

At the close of the 19th century Japanese sculpture began to make a new start under the influence of the West. At this time plaster-modelling and casting by Western methods were introduced.

The department of sculpture in the Imperial Academy of Fine Art is now composed of the following eminent sculptors :

Tatehata Taimu, Naito Shin, Yamasaki Choun, Asakura Fumio, Saito Sogan, Kitamura Seibo, Hirakushi Denchu, Sato Chozan, Fujii Koyu.

Heian: 10th-12th C. -- Yakushi Nyorai (deity of healing)

Heian: 10th-12th C. -- Yakushi Nyorai (deity of healing) Yakushi Nyorai

Yakushi Nyorai Heian: 11th C. -- Bishamon -- deity who guards temples directions)

Heian: 11th C. -- Bishamon -- deity who guards temples directions) Bishamon

Bishamon  Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin (deity who protects the law)

Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin (deity who protects the law) Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin

Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin

Kamakura:1185-1333 -- Shukongo Jin  Kamakura: 1185-1333 -- Nyorin Kannon (deity of compassion, wish granting)

Kamakura: 1185-1333 -- Nyorin Kannon (deity of compassion, wish granting) Kamakura: 1185-1333 Fudo Miyo-o

Kamakura: 1185-1333 Fudo Miyo-o  Fudo Miyo-o

Fudo Miyo-o Kamakura: 1185-1333 Jizo Bosatsu (deity of compassion)

Kamakura: 1185-1333 Jizo Bosatsu (deity of compassion) Jizo Bosatsu

Jizo Bosatsu