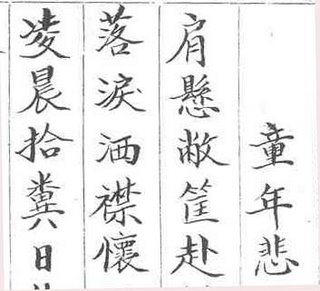

Art of the Chinese Gentleman

I'm sure that those who practice this art (and can read it !) are in a much better position to evaluate it than I am --- but it's excellence jumps out at me -- just like an instrumental solo on a musical recording (and I can't play any instruments either)

These examples are not as spectacular/florid as those of Xugu , who seemed to have modified his practice to accommodate the mood of each painting to which it was attached.

But then, Xugu was a professional artist, while Wang Rui Fu, the creator of this calligraphy, was professional bureaucrat of the old school -- i.e. he was a Confucian gentleman.

But then, Xugu was a professional artist, while Wang Rui Fu, the creator of this calligraphy, was professional bureaucrat of the old school -- i.e. he was a Confucian gentleman.Unfortunately for him, the 1960's was not a good time for Confucian gentlemen in mainland China, and Wang Rui Fu was locked in a cell for five years -- during which time he wrote and memorized (there was no paper) the poetry that he later recorded with the attached calligraphy.

(It's quite a story -- since as a high ranking party official, he had helped design the prison into which he was later interred -- and in his youth, he and his wife had been young revolutionaries who marched with the Red Army during the civil war)

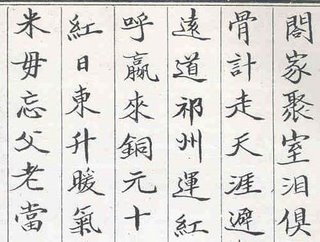

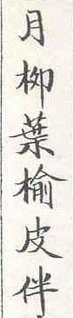

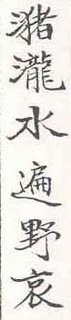

These characters are really elegant, aren't they? (and the actual letters are incredibly small - about 1/2 inch)

These characters are really elegant, aren't they? (and the actual letters are incredibly small - about 1/2 inch) And though he wasn't a professional artist, my friend Ming's father practiced them every day of his un-incarcerated life.

Will Confucian values survive into the next generations ?

I don't know -- but at least in aesthetics, they present an educational model that is vastly superior to visual "art education" as we now know it.

5 Comments:

Doing something every day... What we couldn't do, then.

this pleases me more than Xugu, and I do find something rather cute (i was recently severely upbraided for using that word, but it really does seem appropriate here) about the plant-like messiness around the edges -- the lines feel like fresh grass with unruly tips, like the shoots of a vine looking for something to latch onto. it is certainly original, and, given 3000 years of experiementation, that is quite an achievement. but this isnt my favorite calligraphy. it lacks solidity and yet at the same time isn't particularily inspired/flighty. it's a little weak, really, a little... wishy-washy. a little uncertain of itself. like a receding chin. :)

Cahill, btw, about whom i have been writing over at the Cafe, is a good place to read about something you mention here -- the role of confucian scholarship in Chinese art; which he thinks was tendentiously misrepresented and is now misunderstood as a result of that misrepresentation; like Cahill, i don't think there is much to this art that is Confucian (or Buddhist, or anything); like every art its excellence resides in daily practice (or frequent consumption, or both); and can (theoretically) be as easily done by a social-democrat or a communist or an atheist. (though, not this atheist, for sure; i may have a good hand, but this is still several light years ahead of my best work). thanks, I enjoyed this.

Thankyou, both, for your comments.

Is it possible, Sir G, for you to post some of your favorite examples of this art over on Heaventree ? I'd really like to see the examples you like the best.

I suppose I'll eventually have to read what Cahill has to say -- but I'm wondering whether there any non Confucian societies where the entire ruling class (not just its religious types) was trained and required to practice excellence in calligraphy.

I just read a charming moment in "Tale of Genji" where Genji's young wife glances at a letter written by one of Genji's (many) lovers -- and noticing the quality of the brush work -- KNOWS that she is in trouble.

Regarding your last question: yes, Japan for instance (it stopped being a Confucian society just about the time the Tale of Genji was written), and then never went back, but good calligraphy remains till today a mark of gentleman.

Elsewhere, the upper classes seized on other artistic pursuits of excellence: in the 19th century in Europe we played the piano; in Persia, Turkey, and India they wrote poetry.

Yes, OK, perhaps I will make a post about Chinese calligraphy then. By popular demand. :)

I will have to defer to your authority here, Sir G --- and

acknowledge that Confucian scholarship had little respect for the soldier -- who soon after the Age of the Shining Prince, came to

dominate Japanese life for the next 700 years.

But if we Google "Japan Confucian values" (isn't the Internet wonderful ?) we get about 40,000 hits -- beginning with, for example, "in the Meiji period, the newly introduced national education

system helped spread Japanese Confucian values to a wider range of people"

And ... I'm also wondering whether the decline of Confucian scholarship in Japan coincided with a declining emphasis on calligraphy.

For example -- even the aggressively anti-Confucian leaders of the Communist revolution (from Chairman Mao on down to Ming's father) were proud of their calligraphy -- and I wonder if the same would be true of the Japanese political class of recent times ?

Post a Comment

<< Home