El Greco - Ambition and Defiance

El Greco, "Assumption of the Virgin", Art Institute of Chicago

If Modern Art is a religion, the Art Institute of Chicago is one of its cathedrals and El Greco is its earliest prophet. Not that he or anyone else recognized him as such for about three hundred years — but that, in retrospect, he was the earliest post-Renaissance painter to apparently set an angular formal expression above the demands of mimetic naturalism. And he was fierce - which early Modernists liked so much more than soft sentimentality. And he intermittently broke conventions of portraiture, figuration, and pictorial space.

With it’s commanding “Assumption of the Virgin” (shown above), in the collection for about a hundred years, it’s about time that The Art Institute mounted a career spanning El Greco exhibition - and I have written about this show in New City

You might notice that the address of the New City link includes the following judgment: "the-long-awaited-el-greco-exhibition-at-the-art-institute-of-chicago-lacks-spirit". That was the title originally given to my review by the editor - based on my negative critique of the many devotional pieces in this show executed by the artist's assistants: "they have the flavor of El Greco’s eccentricity without the power of his spirit."

As one visitor to his studio noted, the artist kept a tightly locked room full of original versions of various themes. Presumably, customers could then select a theme and have a copy made in whatever size they chose - as one might for a suit bespoken from the tailor. Good for business -- not necessarily good for art - even if these devotionals were above what was locally available from other artists at that time.

I didn't mention it in the review, but I also have a problem with many of the pieces that do have the artist's fiery spirit - but fail to conflate it with the weight and solid volume that El Greco was borrowing from the leading Roman artists of the time like Michelangelo. The results often feel clumsy and painful to me. In the large altarpieces like the "Assumption", that does not appear to be a problem. It's those ten or so altarpieces that are the amazing legacy of this artist. The only way to experience most of them is to travel to Toledo.

**********************************

In this voluminous post

-- made ever longer by the isolation of Covid 19 -

I offer a painting-by-painting discussion

of the exhibition at the Art Institute

followed by

a paragraph by paragraph examination

of Roger Fry's essay on El Greco

followed by

Elie Faure's discussion of the artist in Chapter Four

of his History of Art : the Spirit of Forms

**********************************

Below are some more thoughts about some of my favorite pieces in the show,

View of Toledo

Landscapes offer relaxation - cityscapes offer stimulation -

this offers both, and may be the first portrait of a city ever done.

Portrait of Frey Hortensio Felix Paravicino

And this may be the first psychological portrait ever done -

presenting the man as the artist experienced him face to face,

rather than as he would like to be presented to the world.

I just learned that John Singer Sargent

advised the Boston Museum of Fine Arts to acquire it.

It’s not the kind of portrait that either artist usually painted.

Sargent, portrait of Joseph Jefferson

(on display in the A.I.C. Sargent exhibition two years ago)

Most Sargent portraits portray well born women as elegant ladyships - but here he painted an actor whose puckish personality must have captivated him - just as El Greco must have enjoyed the company of the neurotic poet-monk-courtier who admired his paintings.

Many of the other portraits in this show, especially of saints, seem too perfunctory. I wish the show had included the St. Jerome from the Frick.

Vision of St. John

I love this crazy thing - regardless of the subject matter attributed to it.

I would call it "St. Augustine" - equally thrilled and dismayed by carnality.

The Holy Face

The Trinity

These are some other pieces from the high altarpiece

made for the Monastery of Santo Domingo Antiguo.

The Trinity was not designed to be seen at eye level.

It needs to be hung way up above the Assumption -

and photos of the reconstructed altarpiece

reveal that it would look very good there.

Adoration of the Shepherds, Prado

As a narrative, it's way too goofy for me.

The artist and his floating son seem to be the center of attention.

As a tiny reproduction, it's a highly charged abstract design.

As a ten-foot painting that dominates a room,

it's insufferable.

********* and here's the rest of the show*************

Adoration of the Shepherds, 1567

Overall, a bit murky,

(As Holland Cotter put it)

But as an abstract design,

it does feel dynamic - especially

in the celestial rondel at the top

Variation done on copper

dated ten years later.

It’s hard for me to believe that either of these was done by the same painter

who did the magnificent Assumption in Chicago.

Here is a variation

not included in this show

As gallery signage suggests,

El Greco used this woodcut taken from Titian as a source

St Francis receives the Stigmata, 1567-70

Gallery signage suggests that the artist was struggling

with perspective in the Saint's left arm -

perhaps because the drapery suggests that

the arm is stretched towards the viewer

while its length suggests that it is parallel to the picture plane.

I have more problem with his brother's left arm in the lower left.

The figure handles its space so awkwardly

I could barely recognize it.

All of which is irrelevant to its witness to the miraculous.

Here’s a version that I like much more .

It was not included in this exhibit however.

Here's a variation from about the same time

that I enjoy much more.

(not included in this exhibit, however)

Quite distant from the numbing sweetness

that would become so prevalent

in Spanish religious art.

The Entombment (1568-1570)

I like this one more than the previous,

especially the lively details below,

but still.....

Christ Carrying the Cross, 1570-71

There are other El Greco variations on this theme

that are less tame.

This belongs in a rectory, not an art museum.

Annunciation, 1576

The gallery signage suggests that this piece combines the "lively, fluid brushwork" of the Venetians with the "bright color palette and weightiness" of Michelangelo and other Romans.

None of which impresses me in this piece -- especially the "weightiness" , or lack of it, in the figures.

The "Annunciation" at the Art Institute proves that El Greco was capable of giving his figures inner dynamics and solidity -- but in this painting he apparently did not feel the need to do so.

Annunciation, 1597-1600

Here's a later, and much larger, version of the same theme.

Wow! It's full El Greco Wacko.

It doesn't look like Venetian or Roman styles of painting

are involved any more.

Lamentation, 1570’s

Gallery signage tells us that

‘To create the Lamentation El Greco turned to a famous drawing by Michelangelo....in his dramatic interpretation the artist emphasized the physical weight and agitation of the figures and heightened this effect with a stormy sky”

There certainly are some similarities to the drawing shown below.

And there’s plenty of agitation.

But I would also say that it’s a clumsy, depressing mess.

The Michelangelo drawing was presented to his fellow poet, Vittoria Colonna.

Notably, the man appears to be as old, or even older, than the woman.

And he appears more exhausted than dead,

while the woman seems more concerned than lamenting.

Giotto

Here's my favorite version - feeling more like a lively performance

of professional actors on an eternal stage

than real people facing a calamity.

Giovanni Bellini

The point of this one seems to be the beauty of Christ forever in the world

rather than any sorrow for His death.

12th Century, Macedonia

This one feels more emotional, like El Greco,

but that emotion is more one of piety than despair.

And this is a stronger, more beautiful painting.

Theophanes of Crete, early 16th Century

Wow! this is a near-contemporary of El Greco

and perhaps exemplifies the kind of painting that El Greco was trained to do.

Without the need to encorporate the more three dimensional figuration of Michelangelo to Tintoretto, I di like it better than any of El Greco's small religious pieces.

Petrus Christus

Entombment, 1572

This piece was recently at auction,

hence the luscious detail image.

I don’t remember noticing it at the exhibit-

I’ll have to look for it if the show ever reopens.

El Soplon, about 1570

This is not the first candle-lit scene in Italian painting,

but it does seem to be among the first

that has no subject other than its unusual lighting.

(Leandro Bassano's "Penelope" from about the same time

would be another, though duller, example)

Ten years later El Greco included the candle lit boy in

the following piece:

Fable, 1580

I sure wish this one had come to Chicago!

It's not a genre scene - it's just high spirited goofiness.

Christ Driving the Money Changers Out of the Temple, 1571

Much better in detail than as a whole.

And it’s not really a very serious piece -

at least in a theological context.

With those four cameos in the lower right corner,

three of the most famous 16th century artists

plus a miniaturist who was a personal friend.

What have they got to do with Christ cleansing the temple?

And does anyone else here look like a money changer?

This is one of seventeen (!) versions that El Greco produced

Here's his last version from about 1610. (not in this show).

The stylistic contrast with earlier variations

was noted by Malraux in his Psychology of Art.

Presumably it demonstrates a pure transformation of forms

— without regard to imitation —

as conventional modeling shifts to flamelike Gothic elongation

even as the objects represented remain the same.

It seems to reflect a narrower notion of "money changers".

But why does this Jewish temple

feature statuary of a standing male nude ?

It ended up in a church in Madrid

which uncovers it for viewing only 1-5 hours /week.

I wonder why.

It's furtive, flashy, electric figuration

makes me think of a painter from the following century:

Allesandro Magnasco

Rembrandt, 1635

This version appeals to me much more.

Maybe you could call it social realism.

Who is that scruffy, crazy guy

who’s making so much trouble for the vendors?

The Disrobing of Christ

Wikipedia tells us that there are 17 versions of this theme,

the one in this show was borrowed from the Alte Pinakothek in Munich.

Here's the original, about four feet higher,

still hanging in the Toledo Cathedral.

detail of the Toledo version

The Munich version had some sharp, and probably original, drawing,

but it felt a bit cramped to me.

A scholar has suggested that it was made

in preparation for making the full size version.

detail of the Munich version

Here's the version in Oslo,

It was done several decades later,

and is about half the size of the one in Munich

Bernhard Strigel - c. 1520

Having more of a northern European temperament myself,

this is a version that I prefer.

Jesus as victim - not conquering hero.

St. Francis in Meditation - Art Institute of Chicago

Fine Arts San Francisco

Francis and Leo contemplating Death

National Gallery, Ottawa

As the patron saint of Toledo, St Francis

had seven convents and three friaries in the city.

None of these pieces appealed to me -

perhaps because they aimed at provoking a

sentimental kind of devotion.

Zurbaran, 1650's

I'm more enthusiastic about the severity, mystery,

and solidity

of Zurbaran's versions.

Christ Taking Leave of his Mother

This sentimental piece comes from a convent in Toledo,

and should quickly be returned there.

Penitent Magdalene, 1577, Worcester Museum

1585, Nelson Atkins Museum

Both of these are in the bug-eyed school of toxic sentimentality -

but the 1585 version is just a little bit trashier.

William Bouguereau

Here’s a 19th century version

of lurid sexual shame.

Yuck.

Donatello

By contrast,

here's a Magdalen who's truly penitent.

But why is a sex worker in greater need of penance than anyone else?

And why did the Roman church ignore the gospels

and start teaching that Mary Magdalen had been a whore?

There are four versions of this image of St. Dominic.

The one shown above (not in this exhibit) looks rather morbid.

This one, from a private collection in Madrid came to this show.

I didn't notice it in my two trips to the show,

but it appears to be much better -- so I'll look for it next time.

St. Peter ( Phillips Collection)

Penitent St. Peter, San Diego Art Museum

Both of the above versions hung in this exhibit.

The expression on the faces is quite different.

Which kind of guilt do you prefer? Sadness or despair ?

Holy Family, (Hispanic Society) 1580's

Holy Family, Cleveland Museum, 1590's

I can't stand either one,

but the one from Clevelend

is way way better.

Portrait of a Man, 1575 (National Gallery Denmark)

Perhaps, at one time,

this was a beautiful painting.

Fugitive color? Over cleaning ?

It certainly appears dull and perfunctory.

Maybe.. that's how the guy was.

Portrait of Trinitarian Friar 1605, Nelson Atkins Museum

Much more expressive than the above.

And is that a television remote control that he's holding ?

I think El Greco liked the Trinitarians.

He painted at least three of them.

Portrait of Pompeo Leoni, 1577-80

This one also appears to be in bad shape.

The above image from Wikipedia has been thoroughly Photo-shopped

in a futile attempt to make it more exciting.

Pompeo Leoni - Portrait of Phillip II

I kind of remember seeing this at the Met,

impressive but repulsive.

It's hard to be king.

Portrait of Antonio de Covarrubias, 1600 (Louvre)

He was a learned friend, and the portrait looks good

- but can't remember seeing it.

Another one to look for when the museum reopens.

Portrait of Francisco de Pisa, 1610

Nor do I remember this one.

Perhaps that’s because such a fearsome visage

needs a room all to itself.

Here are my favorites among

those portraits not included in this show:

Self portrait?, 1600, the Met

Portrait of Cardinal Fernando Nino de Guevara, 1600. The Met

Portrait of Alonso de Ercilla y Zuniga, Hermitage

St. Simon, 1610-14 , Indianapolis Museum, workshop

El Greco Museum, Toledo - detail

1576-8, Private collection

This show includes three paintings of Christ on the cross.

Above is the earliest.

I like the mood of ominous conflated with miraculous.

but ..

the only reason to view such a thing is its attribution.

Here is a slightly different variation

According to the auction house where it recently sold,

there are two others.

Michelangelo, 1538

Gallery signage tells us that El Greco borrowed

contrapposto from the above drawing -

but I don't see as much twist in his torsos.

Michelangelo's Christ has mass and is earthbound,

while El Greco's is rising up like a flame.

Christ on Cross, 1600-14, Getty

Cleveland Museum

I like this version so much better than the other two,

especially for the background

especially for the background

Louvre, 1580-90

This one struck me as a clumsy mess.

The two patrons at the bottom

feel like they were added after the rest was finished.

Titian, 1555 (detail)

This went into the Escorial

so possibly El Greco saw it.

Much more grim than El Greco.

Grunewald, 1515

Grimmest of all,

this is my favorite treatment of the theme.

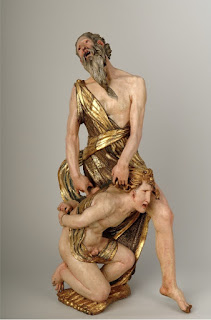

The show also included the above wood carving.

I can’t see any connection to the paintings

other than subject and period

Here’s another 16th c. Spanish sculptor for comparison.

Juan Martinez Montana’s, 1605

Juan de Mesa y Velasco (1583-1627)

Juan de Mesa, 1618

And here are some more pre-Renaissance favorites,

the Medieval Spanish piece above is at the Chicago Art Institute

Annunciation, 1596-1600, Bilbao Museum

This is a small copy of a ten-foot altarpiece.

At full size it's probably spectacular.

At 45 inches, though, it's too busy -

even if executed by the artist's own hand.

Will museums ever present a special exhibition

of life-size photo-reproductions of the great altarpieces?

That could be so much better

than small copies,

even if made by the artist himself.

than small copies,

even if made by the artist himself.

St. Luke Painting the Virgin, 1560-67

Luke's right hand in front of his painted Virgin seems rather awkward.

It appears to coexist in two contrasting pictorial worlds.

It's a shame the surface is so badly damaged.

The Visitation, 1609-13

Not very satisfying - was it finished?

But there is an eerie, prophetic strangeness

about this meeting of these two gravid women

that I can't find in any other depictions

of this theme.

of this theme.

Dinner in the House of Simon, Art Institute of Chicago, 1608-14

Jorge Manuel ( El Greco's son), Hispanic Society of America, 1607-[21

Neither one of these variations is now attributed entirely to El Greco.

I've never liked the one in the Art Institute.

His son's version feels less jumbled.

Jorge Miguel: Noli Me Tangere

I can't find where El Greco ever did this theme,

so I suppose his son, Jorge Miguel, invented this interpretation.

Very romantic.

Presumably, Mary Magdalene has touched Jesus before.

Richard J. (Dick) Miller

My father's version is more -- well -- it speaks for itself

(as seen in our backyard at 2823 Erie, Cincinnati)

Titian

This one is my favorite

Resurrection, 1597-1600

I sure wish the Prado had lent this nine-foot vision to the exhibition.

Laocoon, 1610-14

Sadly, this piece did not travel to this exhibit,

but it's such a wonderful thing

this discussion cannot conclude without it.

It's the artist's only known treatment of classical mythology

apparently done just for the wonder of it.

A sense of infinite wonder.

The form, when seen close up, is more like an electrical field than a solid mass.

I love the space of the cityscape within the oval snake.

I can’t help but thinking:

“THIS is modern painting!”

....yet it is still so different from anything in the twentieth century.

It’s a social, not a personal statement,

but unlike social realism, it’s reality is not earthbound.

To borrow a notion from Roger Fry (discussed below),

El Greco was not just ahead of his time,

he was ahead of our time as well.

******************

"El Greco, Modern Augerer, Stirred Mobs to Battle",

Roger Fry was an outspoken champion of El Greco in the early twentieth century,

back when his paintings were beginning to enter American museums.

The above title of Kramer’s essay pays homage to the Roger Fry essay quoted below.

Kramer also noted that

"I have not attempted to “review” the current El Greco exhibition at the Frick Collection.

To do so would be an intellectual impertinence."

Hurrah for Mr. Kramer.

It’s not unusual for an art journalist to avoid passing judgment on an iconic old master,

but it is quite unusual for him to announce it.

Neither Fry nor myself, however, have been so modest.

Below is the text of Fry's discussion

of "The Agony in the Garden"

which had just been acquired by the National Gallery in London in 1920.

Agony in the Garden, National Gallery, London

MR. HOLMES has risked a good deal in acquiring for the nation the new El Greco. The foresight and understanding necessary to bring off such a coup are not the qualities that we look for from a Director of the National Gallery. Patriotic people may even be inclined to think that the whole proceeding smacks too much of the manner in which Dr. Bode in past ages built up the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, largely at the expense of English collections. Even before the acquisition of the El Greco there were signs that Mr. Holmes did not fully understand the importance of “muddling through.” And now with the El Greco he has given the British public an electric shock. People gather in crowds in front of it, they argue and discuss and lose their tempers. This might be intelligible enough if the price were known to be fabulous, but, so far as I am aware, the price has not been made known, so that it is really about the picture that people get excited. And what is more, they talk about it as they might talk about some contemporary picture, a thing with which they have a right to feel delighted or infuriated as the case may be—it is not like most old pictures, a thing classified and museumified, set altogether apart from life, an object for vague and listless reverence, but an actual living thing, expressing something with which one has got either to agree or disagree. Even if it should not be the superb masterpiece which most of us think it is, almost any sum would have been well spent on a picture capable of provoking such fierce æsthetic interest in the crowd.

I doubt that such “fierce aesthetic interest in the crowd ever happened” — but I hope it did. I’ve never seen anything like it in Chicago where crowds in art museums tend to be quiet and submissive in front of gallery signage and electronic audio tours.

That the artists are excited - never more so - is no wonder foe here is an artist who is not merely modern, but actually appears a few steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way. Immortality if you like!.

In this notion of the “modern” as progressive (rather than merely fashionable) , El Greco surpassed not just his predecessors and peers, but today’s artists as well. No wonder Hilton Kramer felt unfit to critique him. It would be like a Christian presuming to critique St. Paul or John the Baptist.

Is this the “modern” of Picasso and Kandinsky or Manet and Degas ? El Greco is known to have appealed to both kinds of artists, although these two kinds were, and remain often adversarial.

What makes this El Greco “count” with them as surely no old master painting ever did within memory? First, I suspect, the extraordinary completeness of its realization. Even the most casual spectator passing among pictures which retire discreetly behind their canvases, must be struck by the violent attack of these forms, by a relief so outstanding that by comparison the actual scene, the gallery, and one’s neighbors are reduced to the hey of a Whistlerian nocturne. Partly, for we must face the fact, the melodramatic apparatus; the “horrid” rocks, the veiled moon, the ecstatic gestures. Not even the cinema star can push expression further than this. Partly no doubt the clarity and balanced rhythm of the design, the assurance and grace of the handling. For however little people may be conscious of it, formal qualities do affect their reaction to a picture. Though they may pass from them almost immediately to its other implications. And certainly here, if anywhere formal considerations must obtrude themselves even on the most unobservant.

So apparently this crowd prefers a violent attack to the more peaceful feeling of a Whistler nocturne. Why can’t Fry just say that this is his personal preference?

The extraordinary emphasis and amplitude of the rhythm , which thus gathers up into a few sweeping diagonals the whole complex vision, is directly stimulating and exciting. It affects one like an irresistible melody, and makes that organization of all the parts into a single whole, which is generally so difficult for the uninitiated, an easy matter for once.

Of what great painting could this not be said? Such universality is one of the principal drawbacks of formalist art criticism. How can the critic say anything new and interesting? The other drawback being that it must ignore so much of what was both intended and evident.

El Greco, indeed, puts the problem of form and content in a curious way. The artist, whose concern is ultimately and, I believe, exclusively with form, will no doubt be so carried away by the intensity and completeness of the design, that he will never even notice the melodramatic and sentimental content which shocks or delights the ordinary man. It is nonetheless interesting to inquire in what way these two things, the melodramatic expression of high pitched religiosity and a peculiarly intense intense feeling for plastic unity and rhythmic amplitude, were combined in El Greco’s work; even to ask whether there can have been any causal connection between them in the workings of El Greco’s spirit.

It’s one thing to say that you, the viewer, are exclusively concerned with form. I might almost say that myself. If a certain quality in the form is not there, I have no interest in the piece at all. But if formal quality does indeed compel my attention, then I become quite curious about content. And I’m not sure that my mind is ever really totally unaware and unconcerned with content (though I must allow that more highly disciplined minds might well be.)

It’s quite another thing, however , to claim that the artist himself was unconcerned with content - especially when that content appears to be consistent from one piece to the next. Such a claim is too absurd not to just be a rhetorical device.

Strange and extravagantly individual as El Greco seems, he was not really an isolated figure, a miraculous and monstrous apparition thrust into the even current of artistic movement. He really takes his place alongside Bernini as a great exponent of the Baroque idea in figurative art. And the Baroque idea goes back to Michelangelo. Formally, its essence both in art and architecture was the utmost possible enlargement of the unit of design. One can see this most easily in architecture. To Bramante the facade of a palace was made up of a series of storyes, each with its pilasters and windows related proportionally to one another, but each a coordinate unit of design. To the Baroque architect a facade was a single storey with pilasters going the whole height, and only divided, as it were, by an afterthought into subordinate groups corresponding to separate storeys.

Church of the Gesu,, Rome

Bramante, Tempietto

Brunelleschi, San Lorenzo

Here Fry is quoting one of Heinrich Wolfflin's "Principles of Art History"

One might notice that he refers to the Baroque in architecture and sculpture, but not in painting Perhaps that’s because one of El Greco's contemporaries was so obviously responsible for the character of 17th century painting. Caravaggio was born 30 years after El Greco and died ten years before him.

When it came to sculpture and painting the same tendency expressed itself by the discovery of such movements as would make the parts of the body, the head, trunk, limbs, merely so many subordinate divisions of a single unit. Now to do this implied extremely emphatic and marked poses, though not necessarily violent in the sense of displaying great muscular strain. Such poses correspond as expression to marked and excessive mental states, to conditions of ecstasy, or agony or intense contemplation. But even more than to any actual poses resulting from such states, they correspond to a certain accepted and partly conventional language of gesture. They are what we may call rhetorical poses, in that they are not so much the result of the emotions as of the desire to express these emotions to the onlooker.

When the figure is draped the Baroque idea becomes particularly evident. The artists seek voluminous and massive garments which under the stress of an emphatic pose take heavy folds passing in a single diagonal sweep from top to bottom of the whole figure. In the figure of Christ in the National Gallery picture El Greco has established such a diagonal, and has so a ranged the light and shade that he gets a statement of the same general direction twice over, in the sleeve and in the drapery of the thigh.

El Greco, detail of "Agony in the Garden"

Bernini

Donatello

Bernini, David

Donatello, David

The above might serve as examples of the dramatic twisting that Fry found more prevalent in the seventeenth century sculpture than in the sixteenth.

Titian, Assumption (detail)

But then you have the above well known figure. It has a strong diagonal that emphasizes a twist even greater than El Greco's Christ in the garden. Painted in 1515, El Greco would have seen it when he arrived in Venice about fifty years later - and it's hard to deny its influence on his own Assumption painted in 1575.

Bernini was a consummate master of this method of amplifying the unit, but having once set up the great wave of rhythm which held the figure in a single sweep, he gratified his florid taste by allowing elaborate embroidery in the subordinate divisions, feeling perfectly secure that no amount of exuberance would destroy the firmly established scaffolding of his design. Though the psychology of both these great rhetoricians is infinitely remote from us, we tolerate more easily the gloomy and terrible extravagance of El Greco’s melodrama than the radiant effusiveness and amiability of Bernini’s operas.

Written two years after WWI and the Influenza epidemic - total 34 million fatalities worldwide - it’s not surprising that many would prefer the gloomy to the ebullient.

Bernini, St Therese

The expressive angularity of the drapery above does resemble El Greco.

But there is another cause which accounts for our profound difference of feeling towards these two artists. Bernini undoubtedly had a great sense of design, but he was also a prodigious artistic acrobat, capable of feats of dizzying audacity, and unfortunately he loved popularity and the success which came to him so inevitably. He was not fine enough in grain to distinguish between his great imaginative gifts and the superficial virtuosity which made the crowd, including his Popes, gape with astonishment. Consequently he expressed great inventions in a horribly impure technical language. El Greco, on the other hand, had the fortune to be almost entirely out of touch with the public - one picture painted for the king was sufficient to put him out of court for the rest of his life. And in any case he was a singularly pure artist, he expressed his idea with perfect sincerity, with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public.

Fry must consider El Greco the artist apart from El Greco the entrepreneur whose studio produced multiple copies to sell to the public. Otherwise, the above is nonsense.

At no point is there the slightest compromise with the world; the only issue for him is between him and his idea. Nowhere is a violent form softened, nowhere is the expressive quality of brushwork blurred in order to give verisimilitude of texture; no harshness of accent is shirked, no crudity of color opposition avoided, wherever El Greco felt such things to be necessary to the realization of his idea. It is this magnificent courage and purity, this total indifference to the expectation of the public, that bring him so near to us today, when more than ever the artist regards himself as working for ends unguessed at by the mass of his contemporaries. It is this also which accounts for the fact that while nearly every one shudders involuntarily at Bernini’s sentimental sugariness, very few artists of today have ever realized for a moment how unsympathetic to them is the literary content of an El Greco. They simply fail to notice what his pictures are about in the illustrative sense.

Was Fry ever sympathetic to Christian content in any artist from Giotto to Michelangelo?

But to return to the nature of Baroque art. The old question here turns up. Did the dog wag his tail because he was pleased, or was he pleased because his tail wagged? Did the Baroque artists choose ecstatic subjects because they were excited about a certain kind of rhythm, or did they elaborate the rhythm to express a feeling for extreme emotional states ? There is yet another fact which complicates the matter. Baroque art corresponds well enough in time with the Catholic reaction and the rise of Jesuitism, with a religious movement which tended to dwell particularly on these extreme emotional states, and, in fact, the Baroque artists worked in entire harmony with the religious leaders.

This would look as though religion had inspired the artists with a passion for certain themes, and the need to express these had created Baroque art.

Luca Signorelli

I doubt if it was as simple as that. Some action and reaction between the religious ideas of the time and the artists’ conception there may have been, but I think the artists would have elaborated the Baroque idea without this external pressure. For one thing, the idea goes back behind Michelangelo to Signorelli, and in his case, at least, one can see no trace of any preoccupation with those psychological states, but rather a pure passion for a particular kind of rhythmic design. Moreover, the general principle of the continued enlargement of the unit of design was bound to occur the moment artists recovered from the debauch of naturalism of the fifteenth century and became conscious again of the demands of abstract design.

"Debauch of naturalism of the fifteenth century" ? I like that accusation! - even if that's the kind of debauchery I like the most.

I'm not sure I grasp, however, Fry's notion of "enlargement of the unit of design" other than in the architectural facades to which he referred. Do both of the above Signorelli paintings exemplify it? Pattern does seem more dominant in the "Last Judgment". Is that because the artist tries to represent an inner, visionary space rather than the natural world ? In which case, design followed religious fervor, or at least dogma -- rather than a "pure passion for a particular kind of rhythmic design"

In trying thus to place El Greco’s art in perspective, I do not in the least disparage his astonishing individual force. That El Greco had to an extreme degree the quality we call genius is obvious, but he was neither so miraculous nor so isolated as we are often tempted to suppose.

El Greco's uniqueness seems best explained by an apprenticeship in a Byzantine style followed by self training in Venetian Mannerism.

The exuberance and abandonment of Baroque art were natural expressions both of the Italian and Spanish natures, but they were foreign to the intellectual severity of the French genius, and it was from France, and in the person of Poussin, that the counterblast came. He, indeed, could tolerate no such rapid simplification of design. He imposed on himself endless scruples and compunctions, making artistic unity the reward of a long process of selection and discovery. His art became difficult and esoteric. People wonder sometimes at the diversity of modern art, but it is impossible to conceive a sharper opposition than that between Poussin and the Baroque. It is curious, therefore, that modern artists should be able to look back with almost equal reverence to Poussin and to El Greco. In part, this is due to Cézanne’s influence, for, from one point of view, his art may be regarded as a synthesis of these two apparently adverse conceptions of design. For Cézanne consciously studied both, taking from Poussin his discretion and the subtlety of his rhythm, and from El Greco his great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme. The likeness is indeed sometimes startling. One of the greatest critics of our time, von Tschudi—of Swiss origin, I hasten to add, and an enemy of the Kaiser—was showing me El Greco’s “Laocoon,” which he had just bought for Munich, when he whispered to me, as being too dangerous a doctrine to be spoken aloud even in his private room, “Do you know why we admire El Greco’s handling so much? Because it reminds us of Cézanne.”

If Poussin was a model for Cezanne, he was one among many, neither the most important throughout his career nor of the same importance in its several aspects or phases; if,on the contrary, he is often represented otherwise, that is the product of an accumulation of distortions and projections whose origin is in his early commentators,not in the artist himself... Theodore Reff, 1960, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes.

I first heard about the Cezanne/Poussin connection about fifty years ago. Looking it up on the internet today, Cezanne is quoted as saying something about trying to “paint Poussin from nature”. As Reff pointed out, however, the origin of that quote is dubious. Regarding his connection to El Greco, Fry himself may have been the first to write about it. The claim that Cezanne “consciously studied both” is only a conjecture - though it might lead to a good discussion of how Cezanne differed from Renoir and Monet - though I would say that those artists also achieved a “permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme.” What great painter didn't?

No wonder, then, that for the artist of today the new El Greco is of capital importance. For it shows us the master at the height of his powers, at last perfectly aware of his personal conception and daring to give it the completest, most uncompromising expression. That the picture is in a marvellous state of preservation and has been admirably cleaned adds greatly to its value. Dirty yellow varnish no longer interposes here its hallowing influence between the spectator and the artist’s original creation. Since the eye can follow every stroke of the brush, the mind can recover the artist’s gesture and almost the movements of his mind. For never was work more perfectly transparent to the idea, never was an artist’s intention more deliberately and precisely recorded.

One problem with these final assertions is that the National Gallery no longer attributes the painting which Fry saw to El Greco. It has now been demoted to being the work of his assistants. A comparison with the version now in Toledo, Ohio might confirm that judgment.

Agony in the Garden, Toledo Art Museum

detail from the version in the National Gallery, London

detail from the version in the Toledo Art Museum

The drawing of the one was driven by strong inner purpose -- the other was driven by a less-than-successful attempt to copy it.

I first saw this version in an El Greco special exhibit at the Toledo Art Museum about 1990.

We drove all morning from Chicago -- and the show was a big disappointment. The "Agony in the Garden", from the Toledo Museum’s own permanent collection, was the only piece I liked. I thought it weird - but still heads above the copies or damaged originals that made up the rest of that show.

Then I just saw it again last month in Chicago -- and I had the same reaction. It's the work of a master - but still it feels more like a Disney cartoon than a sacred narrative. The four equally sized but quite disparate corners troubled me as much as apparently they troubled the savior kneeling in the center.

But if we accept that feeling troubled is the intended theme - I suppose we could call the painting a success. As the full moon is rising, the central figure is in a very tight spot. His fearsome enemies are approaching, his friends have fallen sleep, a large and imposing angel is offering him the cup of suffering that he is scheduled to quench. From a medieval point of view, expressed by many of the images that follow, this is an accepted fact and all is good because it’s in the divine plan for the redemption of mankind.

But what once was considered factual now requires belief - so human psychology now has become an issue. How would we feel if we were put into that situation ? Eventually this more voluntary approach will see most people move away from the church. El Greco, as well as his intellectual friends on Toledo, must have realized that as the church demands faith (the Holy Office of the Inquisition), it proclaims the difficulty and need for it.

El Greco depicts Christ at the very instant he pivots from confusion and raises his eyes upward toward the divine messenger. In most of the earlier versions shown below, he has already made that decision. Tintoretto’s dreaming Christ is the exception.

*****************

It appears that theological controversy has accompanied this story from even the earliest centuries of the Church. Was Christ human enough to fear suffering on the cross? The gospels tell us that he was sweating blood and asked the Father to relieve him of his cup of suffering. But some scholars believe that those verses were added centuries after the gospels were first written. And most depictions of the scene show an angel offering a cup to Jesus, not the other way around.

Above is a glaring exception to that rule.

Duccio

Donatello

Ghiberti

Durer

Giovanni Bellini

Bellini and Mantegna introduce what we might call the magical --

a special, attractive world where wonders may happen.

It would be a wonderful place to be,

but it does not really exist,

does it ?

It would be a wonderful place to be,

but it does not really exist,

does it ?

Mantegna

These details are so beautiful,

dream-like yet rock solid

Contemporary magical-realism

is rather pathetic by comparison

Contemporary magical-realism

is rather pathetic by comparison

Tintoretto

Now the psychology of the savior becomes an issue,

and the moment feels profound and heroic.

He has not done it yet, but

He has not done it yet, but

we know that this gentle, powerful man

will choose to do the right thing.

will choose to do the right thing.

Caravaggio

This is a different moment - the focus is on the human relationship between teacher and errant disciple.

Caraciolo

A similar human relationship - even if an angel is one of the characters.

It looks like the angel is making an argument

and the savior needs more convincing.

It's done by an immediate

follower of Caravaggio.

Delacroix

I wasn't expecting to find Delacroix doing this subject.

The savior seems to be actively resisting his commission

which is closer to the gospels

than to several doctrinal interpretations.

A whole band of angels has become involved.

******************

Elie Faure, "History of Art",

Book Four "Modern Art"

Spain

Alonso Berruguete, "Abraham and Isaac", 1526-1532

Berruguete, Ecce Homo, 1525

I was introduced to Faure's "Spirit of Forms" about fifty years ago - but even way back then, he was already passé. He was a physician who wrote about art -- not a professional academic. And his history of art was more like a history of European civilization than a history of style and art theory.

His project was organized into four volumes - of which the last he called "Modern" and it went all the way back to the sixteenth century in Holland, Flanders, and Spain. (16th Century artists from Italy, like Michelangelo and Titian, were included in his volume about the Renaissance)

The chapter on Spain began with the above sculptor, who, by the way, had a solo exhibit at the National Gallery in February of this year (his first anywhere outside of Spain). Perhaps his reputation is now ascending. It looks like he deserves it.

Luis De Morales, Pieta, 1560

This is the artist whom Faure mentioned just before discussing El Greco.

The sentimental quality reminds us that when El Greco went to Toledo, he began doing Spanish paintings, just as he became an Italian painter when he lived in Rome.

Here is the discussion of El Greco - beginning with an historical setting:

Philip II was certainly not capable of raising his funereal piety to the level of the passion which filled the little church in Toledo with faces made livid by the rush of blood to the heart, and with eyes of fever and of wild adoration, and with bony hands all lifted toward heaven. Otherwise, something great could have resulted from his meeting with Greco. When Theotocopuli arrived in Toledo, hardly twenty years had elapsed from the time that Ignatius of Loyola, his thigh broken and re-broken, had dragged himself to the altar of the Virgin to lay his sword upon it. Don John of Austria was nailing the banner of Christ to the topmast of the vessels which he was to lead to Lepanto. Teresa of Avila had just finished burning the last ashes of her flesh. For forty years she had welcomed the flame of the south, the scorching of the rocks, the odor of the orange trees, the cruelty of the soldiers, the sadism of the executioners, and the taste of the Host and of wine in order to torture and purify, in the fire of all her senses turned back toward her inner life, the heart she offered to her divine lover. Within the country, the Holy Office never allowed the fire to die out around any stake. Abroad, the captains, dressed in black, led their lean men, fed on gunpowder, to fight, rosary in hand, against the Reformation. The Duke of Alba deluged Flanders with fire and blood. The flames of torture and of battles at- tested, over all the earth, the fidelity of Spain to her vow.

And then there is the physical setting of the regional landscape:

The Cretan, who still saw in the depths of his memory the red and narrow gleam lighting up the icons in the orthodox chapels and whom Titian and Tintoretto had initiated into painting in their Venice, where the bed of purple and of flowers was already prepared for royal deaths, brought into this tragic world the fervor of ardent natures in which all the new forms of sensuality and of violence enter in tongues of fire. In reality, this young man of twenty-five years was old in his civilization, a thing full of neuroses centuries old, and subjugated by the first shock of the savage aspect of the country in which he was arriving and by the accentuated character of the people amid whom he was going to live. Toledo is made of granite. The landscape round about is terrible, of a deadly aridity, with its low bare hills filled with shadow in their hollows, with the rumble of its caged torrent, and with its huge trailing clouds. On sunny days it shines with flame, it is as livid as a cadaver in winter. Only occasionally and slightly is the greenish uniformity of the stone touched by the pale silver of the olive trees, by the light note of pink or blue from a painted wall. But there is no rich land, no leafy foliage: it is a fleshless skeleton in which nothing living moves, a sinister absolute where the soul has no other refuge than the wild solitude or cruelty and misery as it awaits death.

"Tongues of fire" : --- What contemporary art historian

would dare to use such language?

Regarding hot arid deserts --

I have traveled through some - though I can't remember

having thoughts of cruelty or misery or waiting for death.

And now we get a discussion of "The Burial of Count Orgaz"

With this pile of granite, this horror, and this somber flame, Greco painted his pictures. It is a terrifying and splendid painting, gray and black, lit with green reflections. In the black clothing there are only two gray notes, the ruffs and the cuffs from which bony heads and pale hands come forth. Soldiers or priests — it is the last effort of the Catholic tragedy. Already they wear mourning. They are burying a warrior in his steel, and now look only to heaven. Their gray faces have the aridity of the stone. Their protruding bones, their dried skin, and their eyes, deeply sunken in their hollow orbits, look as if they were seized and shaped by metal pincers. Everything which defines the skull and the face is pursued over the hard surfaces, as if the blood no longer coursed through the already withered skin. One would say that a cord of nerves went forth from the vital center and was drawing the skin toward it. Only the eye is burning and fixed, expressing the will to reach the fire of death by dint of rendering life sterile. One follows the glance inward, it leads to the implacable heart. The mouths are like slits. The hair is thin through fasting, asceticism, and the slow asphyxiation rising from braziers burning in closed rooms. The wind of the desert seems to have passed over the scene.

When the red robe flooded with gold and the golden miter of a bishop spread forth, on backgrounds uniformly gray and black, the sumptuous memories brought back from Venice and the Orient, one would say that the painter was playing with his power of controlling the voices of the world in order to give more accent to the dull splendor of the gray faces, and to the harmonies of death and dust which mount like a hymn to the silent joy of offering in sacrifice to the divine spirit of life all the joys which it spreads before us. Remorse at having been born pursues the painter until the end, but when he expresses it in his art, the significance which it takes on avenges him for his terrors. Whatever the elements of the higher equilibrium which a great artist pursues — almost always unknown to himself — whether the most completely purified mysticism or the most violent sensualism guides him, he is not a great artist unless he realizes through them those mysterious symphonies in which both the matter and the soul of life seem present and mingled forever with all eternity. It is not necessary that above Greco's groups, spectral angels of superhuman size should arise, or that, behind his drooping Christ there should be enormous grayish clouds which isolate Him from the universe; the somber glow is everywhere, in the raised foreheads, the hollow orbits, the arid earth, and the habits of black velvet. It is in him, the ardent center of all these things, a profound and living poem fashioned by the encounter of obedience and liberty, of the broad and voluptuous world whence he comes with the harshest soil and the most tragic people of Europe, of the severest spirit of western Catholicism with completely disordered memories of Eastern orthodoxy.

It's likely that Faure traveled to Toledo and saw the actual 12x16 -foot painting -- while all that I've seen is reproductions. The overall effect of those small images is rapturous for me - so I'm guessing that the full sized original in a dark, ancient stone church would feel even more so.

But concerning some details -- I feel confidant that the faces of those men attending the funeral are not characterized by : "Their protruding bones, their dried skin, and their eyes, deeply sunken in their hollow orbits, look as if they were seized and shaped by metal pincers. Everything which defines the skull and the face is pursued over the hard surfaces, as if the blood no longer coursed through the already withered skin."

On the contrary, I don't see any eyes "deeply sunken in their hollow orbits". This feels like a lively, varied group of middle aged men -- all of them subdued -- as appropriate for the occasion - but some more wise or wistful or hopeful or compassionate than others. . The two friars on the left are even having a lively debate. And that's how they should look, right? The painting was commissioned by the parish priest in order to remind these living worthies of their duty - and their eternal reward - for donating cash and goods to his church. The painting was a kind of fund raiser. If you give large donations, St. Stephen and St. Augustine may show up at your funeral as well. And wouldn't that help your case as an angel carries your helpless little soul up to divine judgment ?

Never did the Christian ideal express, with greater anxiety, its impotence to divide life into two sections. The spirit tries to tear itself away, but in vain. What is beautiful in the divine forms is always borrowed from the science he possessed of terrestrial form, and it always returns to them.

But the "Burial of the Count Orgaz" appears to me to be a counter example. The beauty in the lower, terrestrial sphere is the sharp, solid, life-like figure and portrait drawing. The beauty in the upper, celestial sphere is the abstract swirl of shapes and colors.

At the end of his life he painted like one in a hallucination, in a kind of ecstatic nightmare, where the preoccupation with expressing the spirit alone pursued him. Deformation appears in his pictures more and more, lengthening the bodies, attenuating the fingers, and hollowing the masks. His blues, his winelike reds, and his greens seem lit by some livid reflection sent to him from the near-by tomb and the hell caught sight of from eternal bliss. He died before realizing the form of the dream which haunted him, perhaps because he himself was too old, and no longer found in his hardened bones and in his irritated and weak nerves the power he had possessed for seeking, in love of the world's appearances, the means of comparing and supporting his vision.

He must be referring to the "Vision of St. John" at the Met. (the reproduction in the book is called 'The Temptation of St. Anthony") -- and the artist did indeed die before realizing all of its form.

And yet, what an effort! When we enter one of those Spanish churches where, on days of service, the gleam of the tapers and the vapor of the incense make us forget for a moment the horror or vulgarity of the images of which we catch a glimpse, we must also carry on with ourselves one of those combats which leave us enervated and somewhat shaken with that intoxication in which the ecstasy of the paradise desired effaces the soul and the body of those who try to forget. He alone could see arms lifted as if to raise the weight of the heavens and to draw aside its veils. Standing at the foot of the Cross, he alone was able to pierce the shadow which rises from all sides like an accomplice to hide the murder; and it is with a terrible glance that he follows the phantom horsemen who enter a hollow road. He alone has seen among those who will to know no more of the earth, forms drawn out as if in prayer, aspiring wholly toward something higher, hands which seem prolonged into supernatural lights, drooping and emaciated trunks, and also young nude bodies which he cannot tear from the innocence of life, but around which circles a phosphorescent glow which comes no one knows whence.

Faure must be referring to the altar pieces still found in Toledo. I've never seen them.

At the remote origin of that invincible elegance which never left him, however much he was gripped by the need to express more than he could, one found the Greek, the Greek of the forgotten ages, the Hellene. The wraith of the gods which still wandered on the shores of the southern sea had drunk a strong wine from the golden cup of Venice and had permitted itself to be carried along, still not entirely consumed even by Greco, to the burning deserts of stone where the aridity of things offers the mind no other avenue than that of death. It was that wraith — it could not die, it had survived the twelve centuries of constraint imposed by the degenerating Orient upon the Byzantine images — over which one would say that there mounts a long pale flame, like those wandering fires which dance upon the marshes. It is the witness of the impotence of genius to detach itself from its roots, and of the majesty which it assumes when it consents to nourish itself from them. Greco must have fasted and worn sackcloth. He must have followed, with bare feet, the processions across the powdered granite with his ankles cut by shackles, bearing a heavy metal cross, and masked with a monk’s hood in order not to have the pride of his humiliation. He must have passed the burning nights, when passion is compelled to roll in the torture of voluntary chastity, so that in the morning he might carry his exasperated strength into the everlivid faces intent on heaven and into the garments, always black, which bear witness to our grief at having lived. No matter. He had a daughter. He loved children and women, and ever the burning shadow and the bare landscape. His whole will to be superior to life crossed and recrossed the powerful center of the life which, when one has felt its burning, sends its lava into death itself and the eternal shadows and the dust of bones.

Such flamboyant penance seems appropriate for a society as systemically cruel and predatory as the ethnic cleansing and culture-crushing of the 16th Century Spanish empire. It's quite far from the quiet piety of Mt. Athos whose traditions informed El Greco's early life.

It's also quite far from most of El Greco's work -- including his portraits and sentimental devotionals - and even some of his last work -- like the rather whimsical Adoration of the Shepherds (Prado) with family self portrait.

Beyond existence, when our memory is burnt out, there is, to be sure, nothing of us that remains. However, if somewhere there is a place where shadows wander, if in some sinister valley there are cadavers which stand upright and living specters which have not yet lost their form, Domenico Theotocopuli alone, after Dante, has entered there. One would say that he is exploring a dead planet, that he is descending into extinct volcanoes where ashes accumulate and a pale half-veiled moon sheds its light. But all of that has been seen by him. Spain presents such aspects under the snow, in winter, or in the torrid days when the sun has calcined the grass, when there is nothing more in space than the vibration of silence coming from nowhere, to lay its deathlike weight upon the heart, and when livid mirages and gloomy metallic lakes are formed and effaced upon the seared horizon.

If any Spanish artist seems to have been to Hell and back -- I'd say it was Goya who lived through military occupation and civil insurrection.

********************

Here are some of El Greco's Spanish contemporaries. Like him, most studied in Italy. Many were born there. There are also artists coming from Flanders, Portugal, or Germany.

Diego de Aguilar, active 1587

Juan de Alfaro, 1668

Nicolas Borras, 1530-1610

Bartolomeo Carducci 1595

Luis de Carvajal 1531-1618

Eugenio Cajes (1574-1634) , 1600

Romulo Cincinato,1583

Romulo Cincinato

Francisco de Comontes, 1530-39

Juan Correa de Vivar, 1559

Juan Correa de Vivar, 1540-45

Andeas de Concha, 1550-1612

Vicente Juan Masip, 1562

Baltasar Etxabe Orio, (c1558-c1623)

Juan Fernandez de Navarette (1526-1579 Toledo)

Pedro Orente, 1616

Francisco Pacheco, 1615

Juan de Penalosa, 1610

Blas de Prado, 1581

Cristobal Ramirez, d. 1577

Vicente Requena 1556

Jeronimo Rodriguez de Espinosa, early 17th century

Martirio Roelas, 1610-15

Alonso Sanchez Coello, 1588

Juan Sanchez Cotan, 1600-03, Toledo

Alonso Vasquez, 1608

Juan de Ucheda, 1603,4

Luis de Vargas, 1561

Francisco Venegas, 1590

Cristobal de Vera, c 1600

Juan De Villoldo, 1516-1551(Toledo)

Juan Zarinena, 1581

Sofonisba_Anguissola, 1573

With its flat, static, doll-like perfection,

I'm afraid that this is the kind of painting

that Phillip II preferred.

That El Greco felt at home in Spain is partly due to his conscious or subconscious awareness of the ever present and perceptible connections, both superfidal and intrinsic, between Spain and the Orient. It is true that the art of El Greco is not entirely consistent; like others he reveals the conflict resulting from the intrusion of a strong and definite personality into a developed and well established artistic tradition, at a great period of European culture. We refer to his amalgamation of sensual and supersensual, naturalistic and quite unnatural, finite and infinite. Of the true Greek sensitiveness to form there is little trace. So far as it is present it reveals the intermediation of North Italian models. The thing that always stands out most conspicuously in El Greco is the Oriental element, the bent toward that which is supersensual and unbounded, toward the Oriental magic of space. El Greco achieves a certain supernatural abstraction of space like that of mosaics with gold ground, in which all the disturbing and aciddental features of concrete space are smoothed over . Whenever in his works space is more exactly defined for any reason, the artist., nevertheless, transforms the actuality, and endeavors to catch the endless sequence characteristic of Oriental art. The fundamental difference between the intuition of El Greco and that of the Spaniards, using intuition in the widest sense to mean trained vision, apperception, and artistic formulation by the imagination, can be shown by innumerable examples. We shall choose only some of the more obvious and striking of these.

El Greco, San Bernadino, 1603

San Bernadino, Jacobo Bellini, 1450-55

San Bernadino, Mantegna, 1450

I may drive past Saint Bernardine's (the Catholic church in Forest Park) several times a week, but it's namesake is not my favorite saint. He was a popular street preacher who railed against the usury of Jews, the Sodomy of Gays, and wealthy people dressing too luxuriously. Contemporary paintings depict him as a desiccated old man.

150 years later, El Greco depicted him as a gentle, dreamy, starry eyed youth - with an emphasis on the three bishop hats that he was offered but turned down.

A wonderful transformation! If this were the only El Greco painting that I ever saw -- I would love him just for making it.

Zurbaran, Saint Francis (vision of Pope Nicholas) , 1640

Let us begin by making a comparison between El Greco's St. Bernardino of Siena and Zurbaran's St. Francis, which exists in a number of versions and represents the saint as Pope Nicholas once came upon him when visiting his burial place. With Zurbaran all emphasis is laid on bringing out the solidity of the apparition. The holy monk is made tangible; though dead he is given an uncanny life. There is about him the same vitality, the same uncanny vividness, the same appeal to the senses (with the peculiar combination of the rawest visual and the weirdest imaginative material), the same enlivenment of the unusual, and the same elevation of almost gruesome objects into sublime art, that we encounter in the works of Velasquez and Goya. The naturalism that underlies this representation of Zurbaran's runs through the whole of Spanish mysticism. The divine is brought home to us and made objective: not only can we see and touch it, but we can almost even smell it. In the case of El Greco the contrary is always found. His St. Bernardino has only approximate human form. Not merely in a physical sense does the saint's head rise toward, even project into, heaven: the body is nothing, the intellect everything. But precisely where the Spanish painters had appropriated an Oriental element, namely, that Biblical trait of moral athleticism involved first in the prophets' mission and later in the saints' and martyrs' championship of God, El Greco as a Greek is the true descendant of his great philosophical forefathers and prefers contemplation and intellectual values-this contemplation, to be sure, is not without the mystic Oriental coloring injected by the Neo-Platonists. The same line of criticism holds good for E1 Greco's representations of St. Francis, which a whole world separates from the St. Francises of Zurbaran or from the St. Jeromes of Ribera. In these comparisons it may be that the Spaniards' pictures seem more banal, but in the long run they prove more vital than the coolly intellectual works of El Greco.

Though El Greco's Saint Bernardine has his head in the clouds - he hardly feels intellectual. He's a dreamer - not a thinker. And he seems to be quite approachable - especially to children.

Zurbaran's St. Francis is a ghostly apparition - a bit weird and scary - and wonderfully effective. The surface is both tangible and unreal.

Ribera, St. Jerome, 1637

Wow ! What a wonderful painting -- and the artist did 44 variations on this theme.

It is not surprising that the theme of the Expulsion of the Money Changers from the Temple had a special interest for El Greco throughout his life. For his temperament nowhere expressed itself so completely as in this scene with its agitated crowd. Although in the earliest versions the artist approaches the European, particularly the Venetian, sensuous treatment of the subject, later on he gives only the quintessence, the deep content of the episode, and, almost omitting to paint the earthly details and almost restricting himself to symbols, he makes the principal feature the overwhelming triumph of the spirit over material things.

It certainly is an agitated - and gesturing - crowd ---- suggesting life on a busy city street.

And the need for violence to get that unruly crowd to attend to higher things.

Perhaps that's not a message that the Spanish church needed to hear at that time.

It is also symptomatic that in his late years El Greco should have chosen, precisely in the case of this subject, to work on a larger scale, as in the monumental picture of the Brotherhood of the Sacrament at S. Gines in Madrid. The genre-like details of Western, mainly Venetian, origin are reduced to a minimum in the later versions of tbe Expulsion, and are given an entirely new symbolic meaning. In the same way, in the other late works of El Greco, the details of genre tend to disappear. This is extremely significant because El Greco's life extended into the very time when, with the growth or the new naturalism, a special interest in genre-like treatment arose. Before we pursue further the comparison of El Greco with Zurbaran and other Spaniards of the epoch of great national art in Spain, let us consider the relationship of El Greco to his Spanish contemporaries. We wish to anticipate and meet the possible objection that comparison of El Greco with Zurbaran is not exactly permissible because the two artists belong to quite different stages in the general artistic development. Although, according to my conception of the differences from generation to generation, the different stages represented in this comparison play no such major part as the fundamental distinctions of race, yet I recognize the difference of the art epochs represented by the two men

Luis de Morales, "Ecce Homo"

El Greco, "Espolio"

El Greco, St. Julian

The Spanish artist who corresponds in a certain sense to El Greco is Luis de Morales. That he cannot measure up to the Greek in the endowments of genius and of artistic temperament is unimportant in this connection, as is the circumstance that he is a little older. Morales is the principal representative of the Spanish Mannerism of the sixteenth century, the Spanish proto-Baroque. Here we can make this as a mere assertion. We still have to discuss later, and at some length, the character of Mannerism as the European style of the sixteenth century. Morales, almost exclusively a religious painter, a creator of Spanish types of artistic and cultural importance, not only an artist of unalloyed seriousness but one of the most outstanding representatives of Spanish melancholy, belongs absolutely to the company of European Mannerists in his choice of format, method of filling the area, proportions, exaggeration of movement, and striving for elegant posture; and he shows, in his own way, his Milanese education, and, especially, his intimate relations to certain Netherlanders. He has that smoothness of form and that definiteness of expression characteristic of all European Mannerists except Tintoretto, who does occupy a unique position. Particular in contrast to El Greco, Morales' clarity and definiteness of statement, and, above all, genuinely Spanish sculpturesqueness are very striking. A comparison of his Ecce Homo with the middle section of El Greco's Espolio, or of his Saint with Donor with El Greco's St. Julian with Donor (Prado, from the Errazu collection),

Exuberance versus melancholy. There's nothing masochistic about El Greco's Christ

Above are two variations of El Greco's Dolorosa.

Both are now attributed to his workshop.

But the one in green has so much more formal sensitivity.

The one in blue belongs in a tourist gift shop.

Luis De Morales

..... or again of his Dolorosa with El Greco's, shows the whole difference between Spanish religious feeling and that of El Greco, between true Spanish composition and that of the Greek.

If I had to pick a nationality for the Morales version, I would say it has the sentimentality of the southern German areas, like Swabia or Bavaria. The El Greco version, however, feels more Spanish to me than either Greek, German, Flemish, or Italian.

And as demonstrated by the list of El Greco's Spanish contemporaries that I showed above - Spanish painting in that time was quite diverse.

Zurbaran, St. Bonaventure Lying in State, 1629

The Burial of Count Orgaz has a certain Spanish flavor in its melancholy, and its portraits are undeniably striking reproductions of real Spanish types; but, taken either as a whole or in detail, the picture is not Spanish in the same way as Zurbaran's St. Bonaventura on His Deathbed in the Louvre. Nor do we refer to the differences that are really due to difference of period. There are other essential differences that transcend the century and remain constant through all periods. We recognize in Zurbaran's work the greater naturalism and the entirely earth-bound individualism of the Spaniard, who tries to get a thrilling and human expression, based on the simple phenomena of sense, and who reveals an objectivity to which any miracle is an exceptional but thoroughly comprehensible proceeding. El Greco's complexity and subtlety, the gentility and refinement of Greek and other Eastern culture, are not to be found in any Spanish painter. In this connection, too, be it remembered that nine-tenths of the Mudejar decorative work executed by Spanish Christian artists represents a vulgarization of the original Arabic. Weisbach has correctly pointed out that El Greco occupied a much debated, but unique and exotic position in Spain. Then, however, be goes on to say that "the spiritualistic in his art was brought to full maturity partly through his own endowments, partly through his contact with the religious feeling of Spain." I believe I have already demonstrated that the religious spirit of Spain had nothing in common with El Greco's. It is no cause for wonder that, on account of the artistic license be allowed himself in the composition of religious themes, El Greco came into conflict with the Spanish theologians. Take for example the lawsuit over the three Maries that in the Espolio the artist put, contrary to the Bible, right beside the action. That a large audience in Spain, nevertheless, took so keen an interest in the religious painting of El Greco is because the intensity of his pictures for the Church was felt, and they were therefore accepted, with all their strangeness, as the Netherlandish pictures had been accepted a century before.

Death appears more final in Zurbaran -- more transitory in El Greco.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home